Reading, Advertent and In—

How Karl Ove Knausgaard—and I too—became a part of the moment

Celia Paul’s recent self-portrait titled “Reclining Painter” (From the New Yorker)

The Feb 3 issue of the New Yorker magazine has a profile piece about the painter Celia Paul by Karl Ove Knausgaard. I like reading prose about art, especially prose written by novelists, whether they be very old and gone, or just old and cherished but somewhat recently gone, or the very much alive and dancing till late into the night.

Knausgaard, not a friend, didn’t disappoint. For instance, he asked why Paul’s painting of a chair seemed alive while the chair itself is, of course, not alive. His answer, consisting of sentences like slow brushstrokes, is that “the painting consists of encounters.” He goes on: “The painting is alive in the sense that it arises out of a process, led and corrected by the artist’s gaze, but also by her ideas, emotions, and expectations, until she considers the painting finished and it is our gaze it encounters.” As a result of this process, “we see not the chair in itself, as that is for sitting on, but the moment it represents, the here and now it lifts forth.”

That is a wonderful definition of art and how we use art to find our connection to the world.

A question that has been animating recent discussions in my postcolonial literature class recently has been: what does it mean to be alive today? And Knausgaard’s framing of art in the manner that he did gave me another way of posing the question about contemporary literature for my students. I tore out the article from the magazine so that I could keep it safe—but where? On my shelf was a book by Knausgaard titled Inadvertent. I thought I would fold the article and slip it between the pages of that book. When I cracked open the covers my eyes fell on a line that I had underlined when I had received the book as a gift: “It wasn’t until I started breaking the rules, showing how something was and should be understood, very precisely and with no room for doubt, and describing people in psychological terms, that my writing came alive.” Again that word—alive!

Inadvertent is Knausgaard’s response to the question “Why I Write.” As I flipped through more pages, I realized that so much from my earlier reading had faded from memory and was lost. Did I remember that Knausgaard in his youth had written a novel that had been rejected? And that when he wrote a second one, a writer-friend told him that it wasn’t any good and he ended up burning the manuscript in the fireplace? I began to read the pages that followed, but I wasn’t so much reading them as rushing past them, because I quickly wanted to see how had it all changed for the twenty-five-year-old Knausgaard.

He had met a friend who told him that his book was going to be published and this felt like a blow to the stomach. A second thing happened. Knausgaard read Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Two years later, he sent a short story to an editor of an anthology who called him to ask if he had anything else he had written. That question was all that Knausgaard needed. He quit his studies, moved to the town in southern Norway where he had been a teenager, and began writing.

After publishing some fiction, and succeeding at it, Knausgaard reached a dead end. Until he began to write nonfiction. The last five or so pages of Inadvertent offer an argument in favor of Turgenev’s Sketches from a Hunter’s Album against Tolstoy’s monumental War and Peace. Turgenev’s book of loose sketches has nothing of Tolstoy’s magnificent novel (“no action, no intrigue, no plot, no great scenes, nothing which taken as a whole develops and rises and falls, and no central characters”) and yet feels more authentic to Knausgaard. This is so because he believes that Turgenev’s people and his descriptions are not a part of anything larger or a longer chain of events; they belong only to their moment and place. If I understand him, Knausgaard is presenting nonfiction as being more alive than fiction—and this is so because nonfiction is limited or more focused or at least more specific, even narrower, in its ambitions.

That is where Knausgaard had arrived after ten years of failing at writing. His worries about form and style, characterization and voice, etc. had all vanished. What he felt foremost was a sense of freedom.

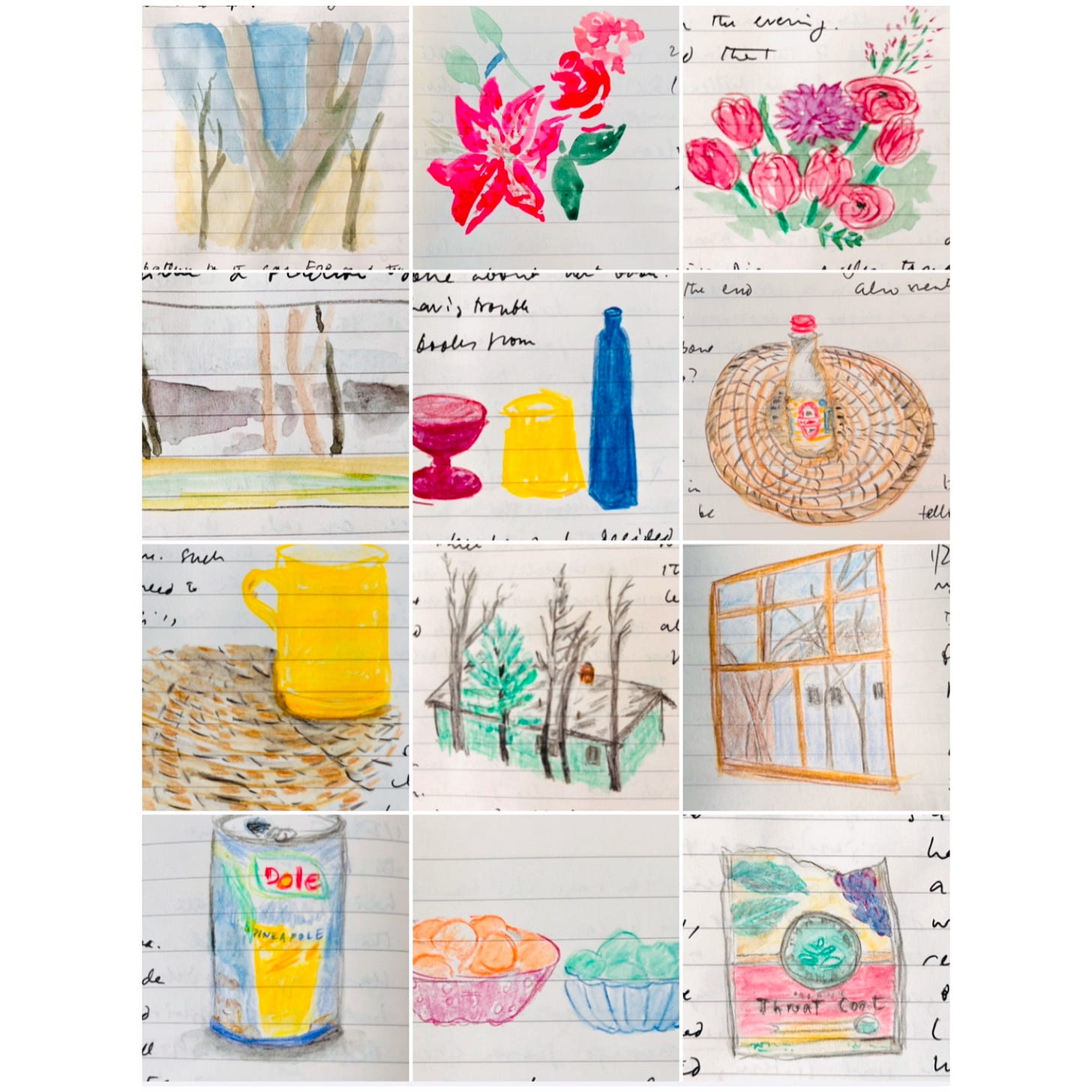

I’m now embarking on a long nonfiction project. I want that sense of freedom too. I will believe almost all arguments in favor of nonfiction at this moment and place. (That said, I still want you to read my novels. My recent two have just been published in paperback. Today’s New York Times Book Review carries a notice about My Beloved Life in its “Paperback Row” announcement. See below.) As my commitment to the moment, I make a daily drawing when I write my morning pages. (But is this even a way of being in the moment? Shouldn’t I be calling my congressman or congresswoman about the Trump/Musk takeover of the country?) When I draw, I feel as if I am centering myself and able to focus. I’m no longer sucked in by the troubled vortex that is news on social media. It is my belief that my writing, as a result, will be more settled and born of a deeper contemplation than purely reactive. This drawing practice has gone on for the last two years or so, but now, over the last few weeks, I have started making drawings in color. I paint what I see on the breakfast table or outside the window. The paper isn’t right for water colors but permits recklessness.

Interesting. The fact that one can't easily separate fiction and non-fiction is particularly evident in writers like Knausgaard.

"They belong only to their moment and place. If I understand him, Knausgaard is presenting nonfiction as being more alive than fiction—and this is so because nonfiction is limited or more focused or at least more specific, even narrower, in its ambitions."

I don't know if I understand or agree with this, but I am happy to have it as a kind of tiny Calder mobile to consider as it hangs there before me. THe power of almost passive gesture in reporting what one sees. But then wasn't K's big epiphany that he was allowed to explain what he says in psychological terms? Anyway, thank you.