What are these Vassar Seniors reading? (Also, what are they drinking?)

The paperback of My Beloved Life has just been released. That is what these students (two of them are also my advisees) are holding in their hands. I am going to be in a conversation with the truly wonderful Katie Kitamura on Wednesday, Feb 5, at the Brooklyn Public Library. Please RSVP here if you plan to come.

(I’ll read a bit from the book and then enter the conversation even though my instinct is to read aloud, with any dramatic flair I can muster, this fantastic review of the book by James Wood.)

I should add that there is a second paperback that is also now out, my previous novel A Time Outside This Time. Katie and I are going to include that book in our discussion because as Katie told me, and I couldn’t agree more, this novel is relevant for Trump 2.0. (Here’s a note on the novel in New Yorker magazine’s “Briefly Noted.” More reviews and interviews here.)

I have always written fiction with the desire to understand what it means to be alive today. (Was this a mantra I read somewhere? Did someone like Henry James say it? I tried to do a search online. One of the links that came up during my search was not about writing but an excellent memoir-essay by Justin Taylor.)

In 2018, by the time Immigrant, Montana was published, I was working on an idea for a new novel. Trump had been elected President in 2016 and every day I would note down in my journal one piece of fake news. (Hemingway’s motto was to write one true sentence each day, “the truest sentence you know,” and I felt that taking note of that day’s lie was just right for the new regime.) I was asking myself questions about the place of fiction in the world of that bad fiction called fake news. The result of this way of thinking was A Time Outside This Time.

In a novel around that time (I just checked, it was 2018, and the novel was Crudo), I read the following lines in a description of a party after a wedding: “Back inside, they were eating more cake when someone shouted Steve Bannon’s resigned. They all checked their phones.” I liked that, not least because I was on a similar track, trying to think of small, private moments in people’s lives and their entanglement with the news of the world outside. The idea was to examine not just the overlap but to mediate the relationship—at one point the novel asks, “How to slow-jam the news?”

In my youth, the entry of the real world in the world of fiction had always provided a jolt. Mrs. Gandhi in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children or General Zia’s presence in Hanif Kureishi’s My Beautiful Laundrette (“But that country has been sodomized by religion” says Nasser to the socialist father in exile in England, the father played by the great Roshan Seth.) With greater maturity also came the appreciation for other kinds of fiction where the hectic world of news was set at a distance, even refracted, as in J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians and W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn.

I’ve been working in the in-between space. I’m thinking here of a Kalam Patua painting which depicts a bhadralok couple presented in Kalighat style serenely eating a meal while behind them on the TV you see smoke billowing out of the Twin Towers.

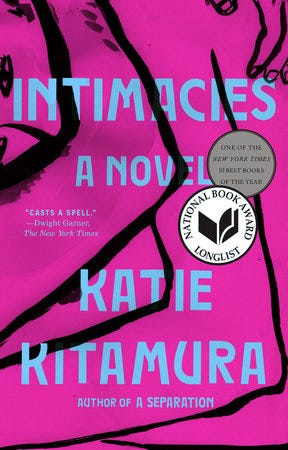

I can also talk here of Katie’s last novel, Intimacies, a Top 10 Book of 2021 at The New York Times. The novel’s narrator is an interpreter in the international court at The Hague; her work at the criminal court brings her in contact with the violence of the world, with genocide. At the same time, she is dealing with feelings of alienation in a new and strange city, and her uncertain, ambiguous sense of love while a relationship develops with a Dutch man who is separated from his wife. What gives the novel its rich complexity is that the task of the interpreter, and the narrator’s meditative reports on her work, bring the reader closer to language, and therefore, as if we were standing before a stained mirror, also closer to life. This is what it means to be alive today. Read this brilliant passage from Intimacies explaining the search for precision or exactitude—in short, for truth:

There was a certain level of tension that was intrinsic to the Court and its activities, a contradiction between the intimate nature of pain, and the public arena in which it had to be exhibited. A trial was a complex calculus of performance in which we were all involved, and from which none of us could be entirely exempt. It was the job of the interpreter not simply to state or perform but to repeat the unspeakable. Perhaps that was the real anxiety within the Court, and among the interpreters. The fact that our daily activity hinged on the repeated description—description, elaboration, and delineation—of matters that were, outside, generally subject to euphemism and elision.

Language! The search for the right words! Language is the river where all writers come to drink water at dawn and then again at dusk. There is a line of Chekhov’s that I think about often: “A cuckoo seemed to be adding up someone’s age, kept losing count and starting again.” I hope to remain alive long enough to write one day a line about the koel’s cry during the afternoon heat in May. But May is still far away. If you are in the area, please come to the event with Katie Kitamura on Wednesday. And pick up copies of the new paperbacks. Leave comments here when you have read them. Let’s talk.

“Language is the river where all writers come to drink water at dawn and then again at dusk.” What a line! 🌻

"What it means to be alive today" reminds me of the title of the Anthony Trollope novel, The Way We Live Now which I read many years ago and think it may be time to revisit. I found this quote about it in Goodreads (apparently from his autobiography)“Nevertheless a certain class of dishonesty, dishonesty magnificent in its proportions, and climbing into high places, has become at the same time so rampant and so splendid that there seems to be reason for fearing that men and women will be taught to feel that dishonesty, if it can become splendid, will cease to be abominable. If dishonesty can live in a gorgeous palace with pictures on all its walls, and gems in all its cupboards, with marble and ivory in all its corners, and can give Apician dinners, and get into Parliament, and deal in millions, then dishonesty is not disgraceful, and the man dishonest after such a fashion is not a low scoundrel. Instigated, I say, by some such reflections as these, I sat down in my new house to write The Way We Live Now. And as I had ventured to take the whip of the satirist into my hand, I went beyond the iniquities of the great speculator who robs everybody, and made an onslaught also on other vices;--on the intrigues of girls who want to get married, on the luxury of young men who prefer to remain single, and on the puffing propensities of authors who desire to cheat the public into buying their volumes.”