Writers' Notebooks

How to do research, and how to borrow—and steal

Penelope Fitzgerald’s notebook in the British library. I made this drawing in April, 2022.

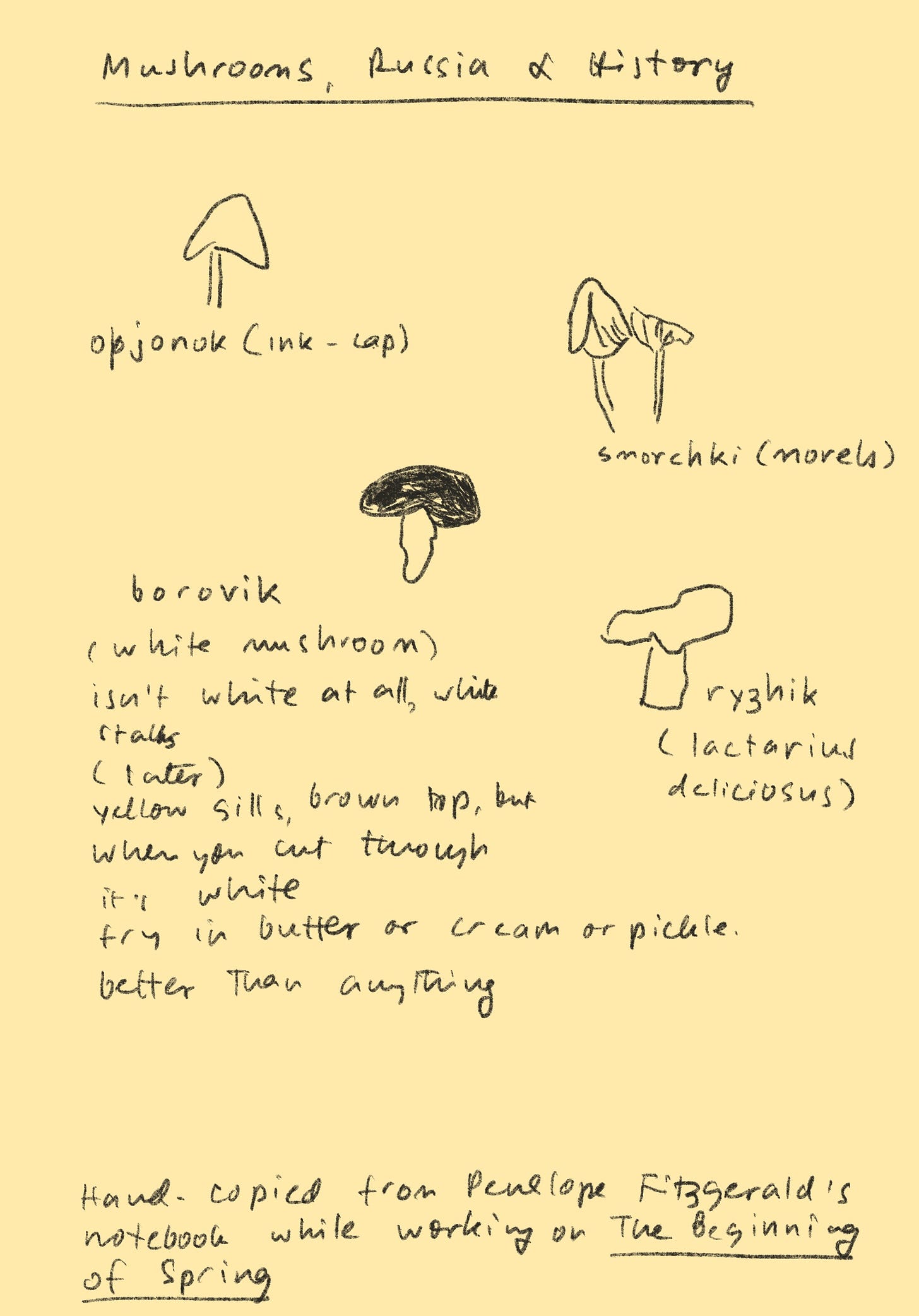

I am interested in writers’ notebooks. They provide a record of thinking. That is what I had written in a piece on Shiva Naipaul’s notebook used during his visit to India after the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Naipaul’s notebook is a 4x6 object identified as ADD MS 89154/11/21 at the British Library in London. But this Substack entry is about another notebook by a different writer. I had read Penelope Fitzgerald’s novel The Beginning of Spring (1988) and found it fine and mysterious; furthermore, I had wondered how she knew small details about Moscow and life there during the years before the First World War. Then, in the British Library, listed under ADD MS 89289/2/17, I found her slim red memo book. Fitzgerald had written down the earlier title for the novel (The Greenhouse) and, in blue ink surrounded by water stains, revealed the first outline of the proposed book: “Harry’s wife leaves him, taking children (one boy 2 girls) with her. In letter explaining this she gives some of the reasons, which describe what it’s like in Moscow. Include vulgarity of Harry’s friends, a Russian merchant, M.” On the pages that follow are signs of the novelist trying to figure out and advance the plot and the story. “Suddenly children are returned—they’re all by themselves at station. Brings them back. Who to look after them? Borrow the governess? … Masha to have troubling effect on Harry. Builds greenhouse now to take his mind off her.” Also on the same page, in block letters, “BEAR STORY.” The bear story refers to a wonderful, dramatic incident in which, at the home of the Russian merchant, a baby bear is given vodka to drink. It gets drunk and wants more. Soon, the bear is wreaking havoc, pulling down the tablecloth, breaking bottles, slurping the spilled drinks. It sprays the carpet with urine. Drawn by the shouting and the laughter, a servant comes into the room and snatching a shovel, throws coal from the fire onto the drunk bear. The bear screams, “its screams like those of a human child.” Fitzgerald’s notebook lists the names of books and articles she uses for her research; there are notes on everything from anarchism in Russia to the repair of dachas, from notes on Tolstoy to annotated drawings of the kinds of mushrooms to be found in the countryside.

All this research gets quite subtly absorbed into the narrative, and I find it instructive. However, what the notebooks don’t reveal—and this I learned from reading Hermione Lee’s excellent biography, Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life—are the more specific ways in which the borrowing takes place. Lee informs us that one of the titles I had seen listed in Fitzgerald’s notes, the travel-guide Baedeker’s Russia 1914, provides so much of the information that appears in the novel, including its opening line: “In 1913 the journey from Moscow to Charing Cross, changing at Warsaw, cost fourteen pounds, six shillings and three pence and took two and a half days.” Here’s Lee: “Sure enough, Baedeker’s Russia for 1914 informs you that the train—going the other way from Charing Cross to Moscow via Warsaw—takes two and a half days and costs £14. 6s. 3d. Baedeker gave her everything she needed by way of maps, place-names, shops, markets, restaurants, parks, churches, stations, concert halls, passport requirements, rules and regulations for non-Russians, the contents of picture galleries (including a paintings by one Yendoghrov called Beginning of Spring) and general thoughts on the city’s atmosphere…” (These lines made me wonder if I had ever made clever and adequate use of Wikipedia.) The more startling revelation in Lee’s book was about the aforementioned bear story. In a book called The Smiths in Moscow (1984) by Harvey Pitcher, Fitzgerald had come across a description of a party where a bear had been given vodka. When her novel was coming out, Fitzgerald wrote to Pitcher seeking permission to use that story. Lee writes: “He was happy to oblige, and a friendly correspondence ensued.” And then Lee slyly goes on: “He would have noticed many other links, too, between The Smiths of Moscow and The Beginning of Spring: the English families’ dacha outside Moscow, set in woods of silver birches, the corruption and obstructiveness of government and police, the assimilation of the English children, all of whom spoke perfect Russian and felt completely at home in Moscow. Fitzgerald raided Smith, too, for the English chaplaincy, the English governess, and the big Scottish department store, Muir & Merrilees.” Then, Lee goes on to list other borrowings.

As I begin work on a new book, here’s my prayer to my gentle muses: teach me please to maintain a notebook! And please give me the strength and guile to borrow freely and imaginatively.

Ever since I first read 'Immigrant, Montana', I've been captivated by the way you weave narratives, photographs, your own paintings, and snippets of poetry and news. Your unique approach nudged me to continue keeping my own commonplace notebooks and journals, collecting the myriad inspirations I stumble upon in my everyday experiences. Your appreciation of other writers' notebooks brings everything full circle, for it's truly enriching to realize how interconnected our inspirations are.