Why Am I Still Teaching Journalism?

A brief report on PEN World Voices Festival

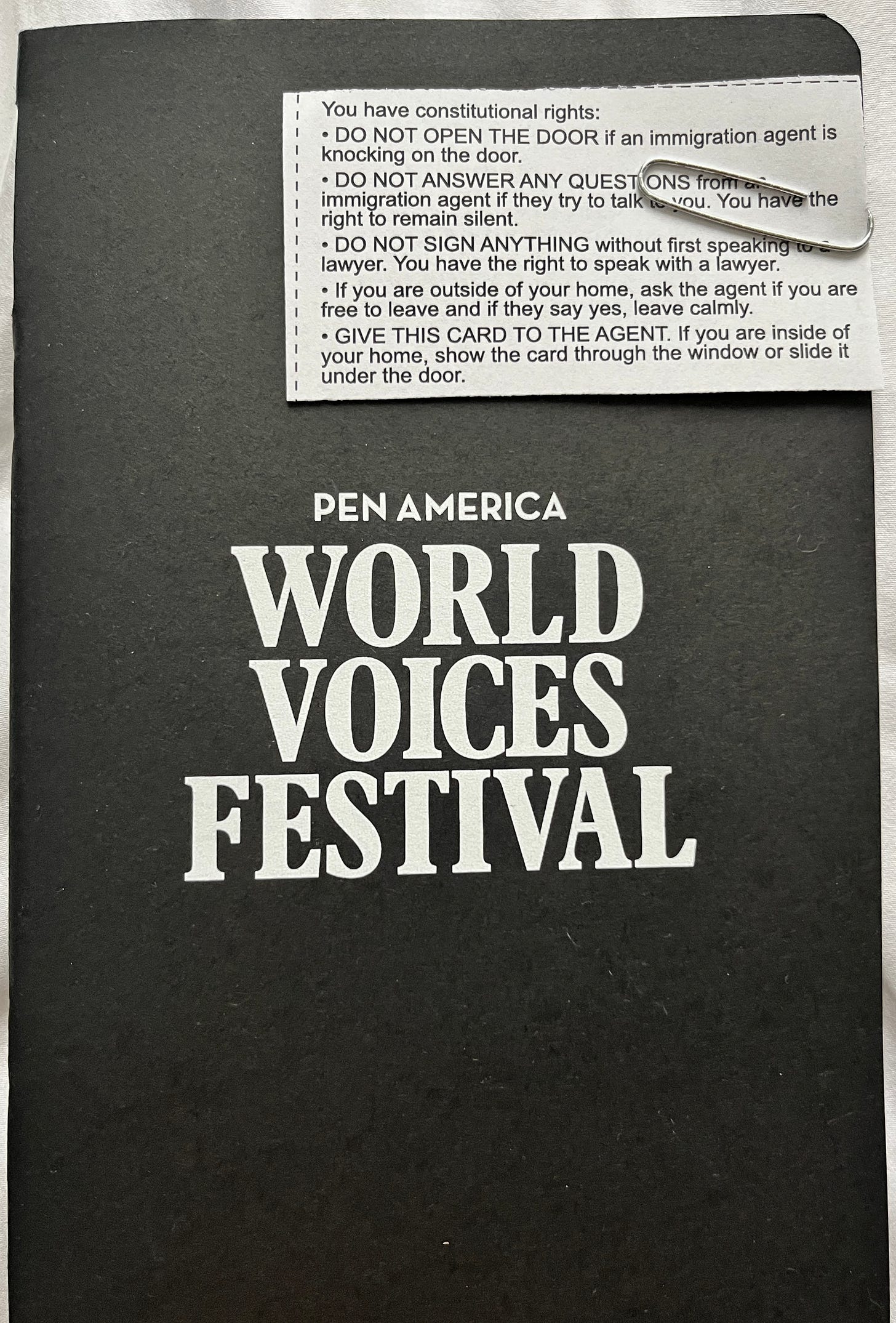

I am on my way back from the PEN World Voices Festival in NYC where I participated yesterday on a panel that foregrounded “how changing political environments reflect the shifting nature of personhood.” Yesterday was also World Press Freedom Day and last evening I attending the closing section of the festival titled “Under Siege: The Perils of Journalism in an Age of State Repression.” As it happens, I’m teaching a journalism course this semester—the question of state repression has surfaced in our class too, particularly when discussing the role of student journalists when members of ICE or police show up on college campuses to make arrests. Two members of the PEN panel last evening were female journalists working under severe conditions in the Philippines and India (Patricia Evangelista and Rana Ayyub) but the third panelist was a male journalist from the U.S. (George Packer) who admitted that while conditions in this country weren’t as extreme for journalists, or at least not yet, people in the press needed to confront the issue of their increasing irrelevance.

According to the Press Freedom Index, India ranks a low 151 out of the 180 countries surveyed. Rana Ayyub began by referring to India’s dismal showing on the various world indices on press freedom. “There is no space for dissidence.” She said that she had needed to get court permission to leave the country. Her bank account is frozen and she has to live with her parents. The latest police case against her is based on a complaint filed against a tweet she had posted way back in 2012. Ayyub pointed out that while social media sites like X allow marginalized voices like hers to have space, this fact is wholly undercut by the amount of misinformation and fake news spread on such sites. Not to mention the relentless and dangerous, vilely misogynistic, trolling of female journalists on such sites. She said that most recently there was a picture of her being circulated where her body had been morphed next to that of Osama bin Laden so that they were lying in bed together.

Ayyub has received awards for her courageous reporting but she said she would rather not be hailed for her bravery. This was because by calling her brave, those who should be doing more absolved themselves of their own responsibility. Also, she wanted to know why she was being forced to operate under conditions in which she needed to be resilient. I was especially struck by her observation that she isn’t even the same person that she was three years ago. Later, I asked Ayyub why this was so. And she said that this is because she is more fearful. She said, Dar lagta hai. She has begun to censor herself. It baffles her that the political culture has been made so poisonous in India that any sign of criticism of the government is seen as anti-patriotic and seditious. And the creed of a dominant majoritarianism means that Muslims are quickly accused of traitorous acts. For example, when Ayyub had fallen sick because of the coronavirus, she was charged with carrying out “Corona Jihad.”

I asked Ayyub about her background: she was born in Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh and grew up in Mumbai. Her father was close to various members of the Progressive Writers’ Association; Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Kaifi Azmi, and Ali Sardar Jafri were among his comrades. When Ayyub told me this, I got a sense of her lineage and maybe also a glimpse into her resilience. When you consider those names, you are immediately in touch with a distinguished record of resistance and a fearless courting of arrests. What a fall it has been! To have your fate now determined by a lumpen mob on social media and their powerful leaders who profit by employing a calculus of hate.

This coming week is our last week of classes. My journalism students are writing their final reports on a host of issues; I cannot claim that all their reports will hold the powerful accountable or give voice to the voiceless, but they do provide a record of what it means to be alive on a college campus in America right now. I want my students to have the tools to tell stories when they go out into the world and to be ready if there is an unexpected knock on the door.

I take heart that you are continuing to teach students journalism, in the fullest sense of the way in which your own work participates in journalism. Thank you for that. And also for illuminating the conditions for the press in India, which I think many of us (certainly me) don't really know what we need to know. You put your gifts to the good work, Ami.

I'm glad to hear that you're still teaching journalism classes, especially at a time like this. I still think about the creative non-fiction class I took with you four years ago.