You have seen the above meme. That lovely quote from Woolf appeared on my social media timelines at the start of this month—and liberated me. I had not been writing or painting—not been immersed in a project—and experiencing mounting guilt. Then, I saw the above diary entry of Woolf’s and felt utterly justified in what I have been doing these past few weeks at the Cullman Center. I had mentioned in an earlier post here that my reading the news about Gita Mehta’s death had led me to a documentary on the liberation of Bangladesh and then a reading of the circumstances of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s murder. Following a friend’s recommendation, I read Boulder, Eva Baltasar’s fierce novella about queer love. (A line from that book that has stayed in my mind: “Language is and always will be an occupied territory.”) A friend posted on Facebook a link to an old article about Girish Karnad’s play Tughlaq; the article brought back memories from my youth of watching Manohar Singh in Delhi in the title role. Even before I had finished reading the article I made a request for a copy of the play and the book was delivered here at the Center that same afternoon. The play led me to purchase Karnad’s memoir which must have arrived by now at my home in Poughkeepsie. Then I embarked on a reading of my friend George Saunders’s craft-book A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, a fine compilation of classic nineteenth century Russian short stories accompanied by George’s analysis of how and why these stories move us. Now and then, I also dip into George’s notes on Substack, where some of those lessons are revisited and new ones explored. In one of the later chapters in his book, George mentioned Victor Klemper’s diaries, I Shall Bear Witness. I quickly requested that from the NYPL and that book too was duly delivered and sits on my desk.

But then, in the middle of this pleasant drift, there has been the explosion of war. Instead of drift, the iron cage. Rage and helplessness at the destruction of life and homes. Even at this enormous distance from the pain and suffering of those immediately affected by the war in Israel and Gaza, we cannot but feel paralyzed, particularly as writers, because we don’t know—I don’t know—what can be said that will make a difference. Not only because the pain is so overwhelming but because the divisions appear so deep and feelings so intransigent. How to produce writing that creates a space hospitable to otherness?

Perhaps proceed by critiquing writing itself. I’m thinking now of a poem by Solmaz Sharif, particularly the following line: “Our poets do not imagine / a screaming /audience. /Our poets are used to padding,/ vinyl, on foldable chairs.”

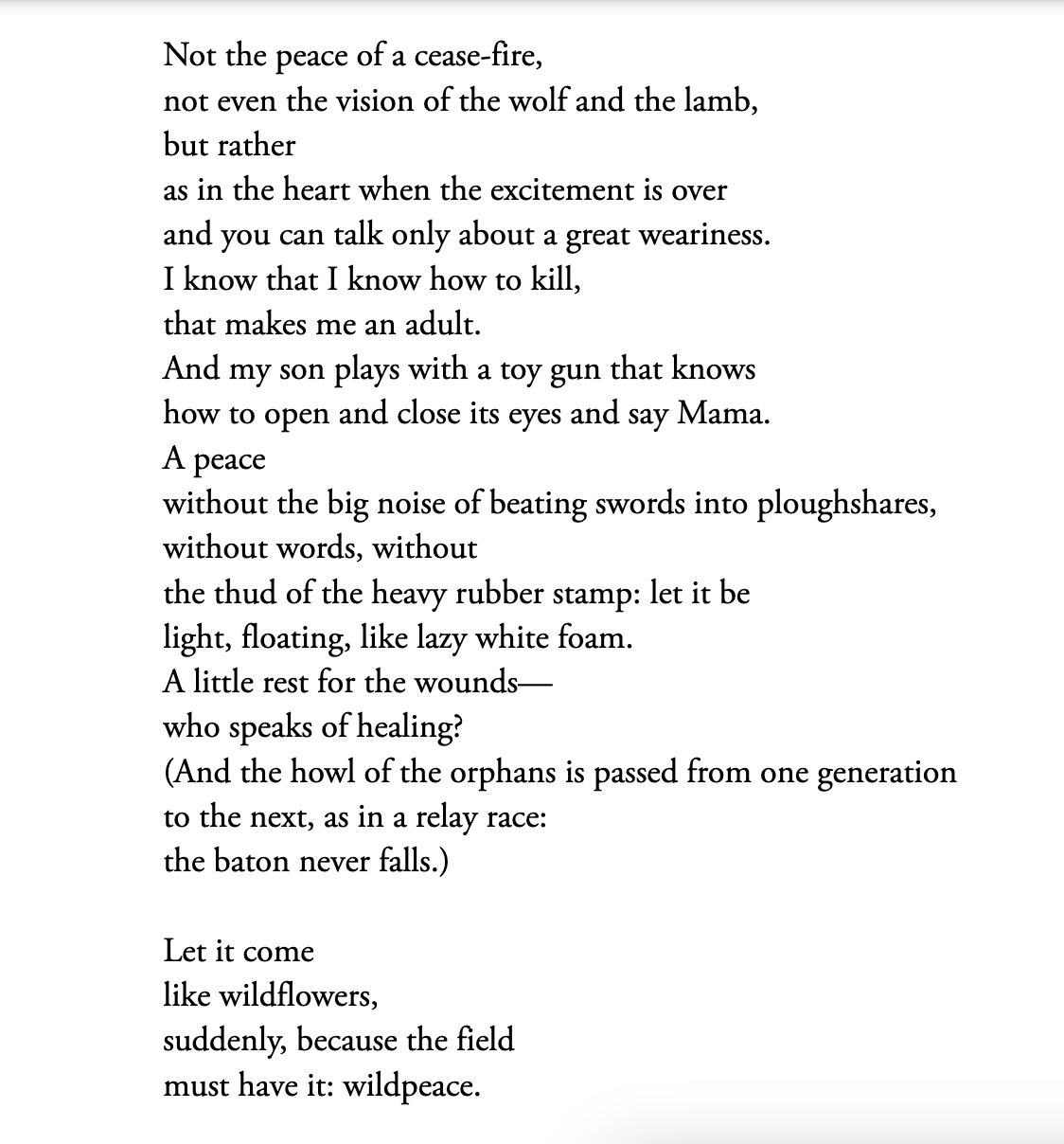

Or simply by imagining the beauty—the lightness—of peace. As in this poem entitled “Wildpeace” by Yehuda Amichai:

Instead of watching the news, I’m reading poems today. Poems offering a different kind of witness than our television cameras and studio achors do. I’m finding a refuge in language, reading, for example, “Vietnam” by Wislawa Szymborska. Or, returning to Amichai, the poem titled “The Diameter of the Bomb.” The plain, final line of this short poem by Randall Jarrell that removes all delusions of glory from the games of war. Perhaps you have your own examples that you can share in the comments.

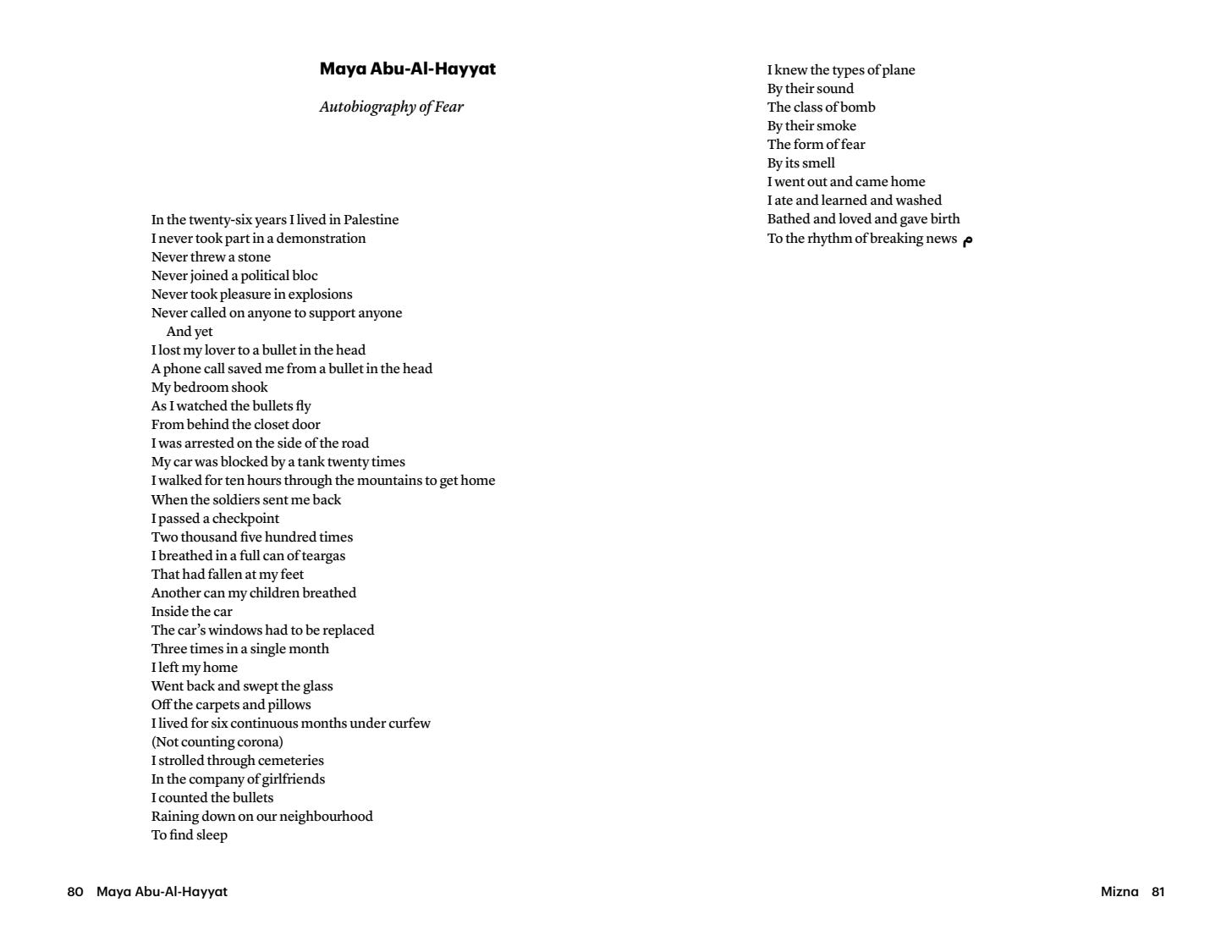

One last recommendation. One of my fellow Fellows here at the Cullman Center is Yasmine Seale who, with what she calls bitterly apt timing, has just this week published her translation of a shattering poem by Maya Abu Al-Hayat in Mizna:

https://www.milleworld.com/palestinian-poems-resistance/

Does the world hear the voices of the Palestinians?

Thank you for sharing the poem by Maya Abu Al-Hayat.

In you book, Writing b̶a̶d̶l̶y̶ is easy, you say you don't understand poetry. I feel much the same way for the most part, but this poem made my skin crawl.