During my break, which is about to end, I read student papers every day. Just a few each day, in order to keep things manageable, taking my cue from one of those cricketers I admire, pacing their innings to meet the target. I made at least one drawing or painting each day, and I also read for class, and when all that was taken care of, I decided to read for pleasure. Long ago, I had started reading Samantha Harvey’s Booker Prize-winning novel Orbital. I was on an airplane, returning from India, and this might sound odd but I decided the language was too beautiful for me to enjoy just then. Not this time, however. In the novel, six astronauts are in space and we learn very quickly that they circle the earth sixteen times each day. In the course of this single day narrated in the book, “they’ll see sixteen sunrises and sixteen sunsets, sixteen days and sixteen nights.” The sixteen orbits serve as the novel’s sixteen chapters. Harvey’s poetic language in this little book, 136 pages in all, is not just beautiful; it is filled with astonishment and incites wonder. Each detail, each observation, appears washed in the sun’s new light or set gleaming like a jewel in deep darkness. Last night, after finishing reading the book, I also read a few reviews: Joshua Ferris in the New York Times notes that “the book is ravishingly beautiful” and one of the many remarkable things that James Wood says about Harvey in the New Yorker is that she is writing “like a kind of Melville of the skies.”

I encourage you to read those reviews and, indeed, to read the novel itself; what I also want to marvel at is Harvey’s research that went into the making of this book. In the acknowledgments, she expresses “gratitude to NASA and ESA for the wealth of information made available.” Of course, no amount of research can yield the imaginative fecundity on display in the descriptions of different parts of the earth as observed from space. That’s my first point.

The second related point is the genius involved in choosing the point of view. Look at the photo above. It is discussed in Orbital. A photograph taken during the 1969 Apollo 11 mission by the astronaut Michael Collins. Here is what Harvey writes about it: “In the photograph Collins took there’s the lunar module carrying Armstrong and Aldrin, just behind them the moon, and some two hundred and fifty thousand miles beyond that the earth, a blue half-sphere hanging in all blackness and bearing mankind. Michael Collins is the only human being not in that photograph, it is said, and this has always been a source of great enchantment. Every single other person currently in existence, to mankind’s knowledge, is contained in that image; only one is missing, he who made the image.” It is difficult not to be struck by this insight and to experience that feeling of enchantment. But this view is swiftly, deftly, undercut in the novel. One of the astronauts in Harvey’s book, remembering the Collins photograph, is unmoved by the claims made about it. “What of all the people on the other side of the earth that the camera can’t see, and everybody in the southern hemisphere which is in night and gulped up by the darkness of space? Are they in the photograph? In truth, nobody is in that photograph, nobody can be seen. Everybody is invisible—Armstrong and Aldrin inside the lunar module, humankind unseen on a planet that could easily, from this view, be uninhabited. The strongest, most deducible proof of life in the photograph is the photographer himself—his eye at the viewfinder, the warm press of his finger on the shutter release. In that sense, the more enchanting thing about Collins’s image is that, in the moment of taking the photograph, he is really the only human presence it contains.” (Oh, how I love the use of a visual story within the larger story I am reading: the visual containing a key to how I am to read the story within which it is contained!) The genius I’m celebrating is Harvey’s choice of the astronaut—a Michael Collins-like stand-in—to register at once the immensity of space and also, in the act of seeing (the book teems with remarkable visual details), the intelligent, quietly sentient human presence behind it.

Which brings me to a point about craft. Readers of this Substack will remember my interest in gathering advice for writers. Here is the latest piece of advice I have collected, this from the writer Rebecca Makkai whose own Substacks are funds of wonderful knowledge:

“Write about the strangest livelihood.” — Rebecca Makkai

P.S.

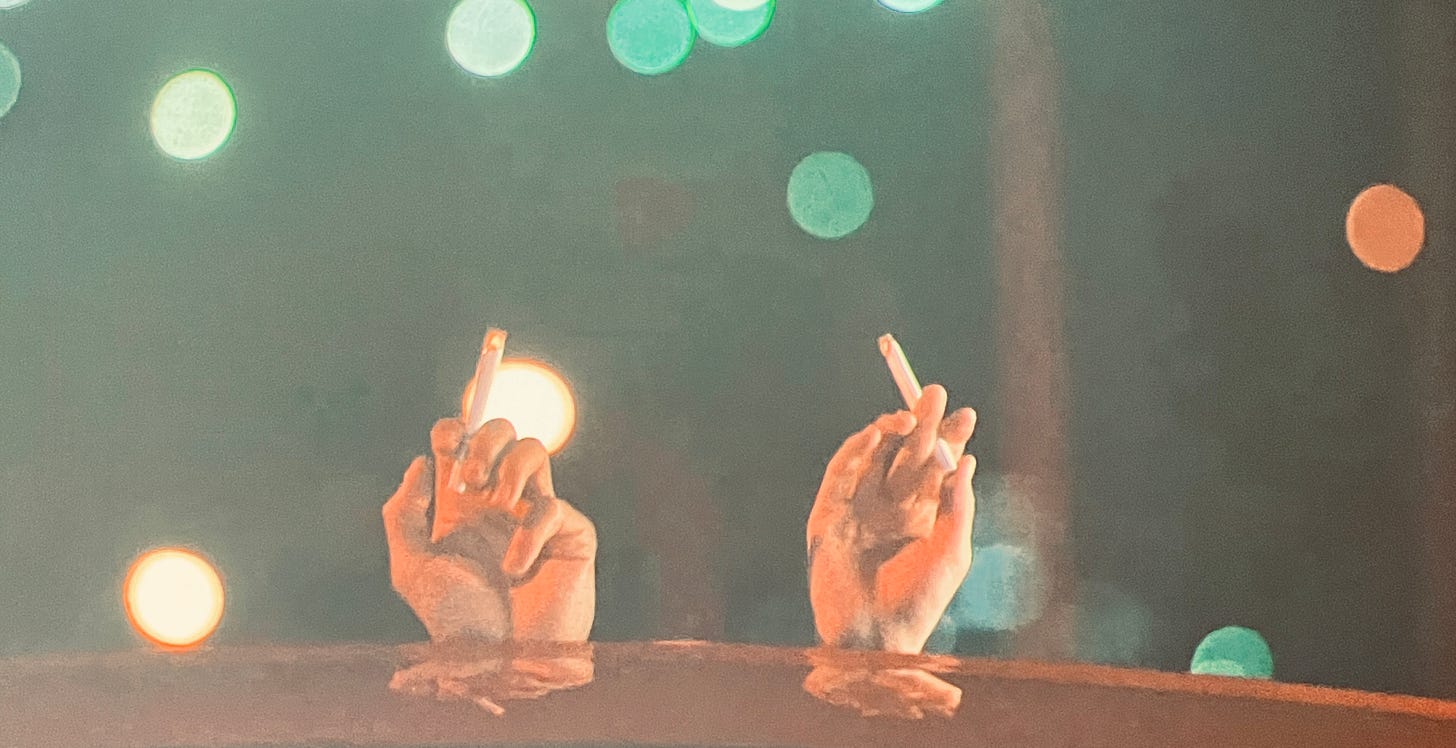

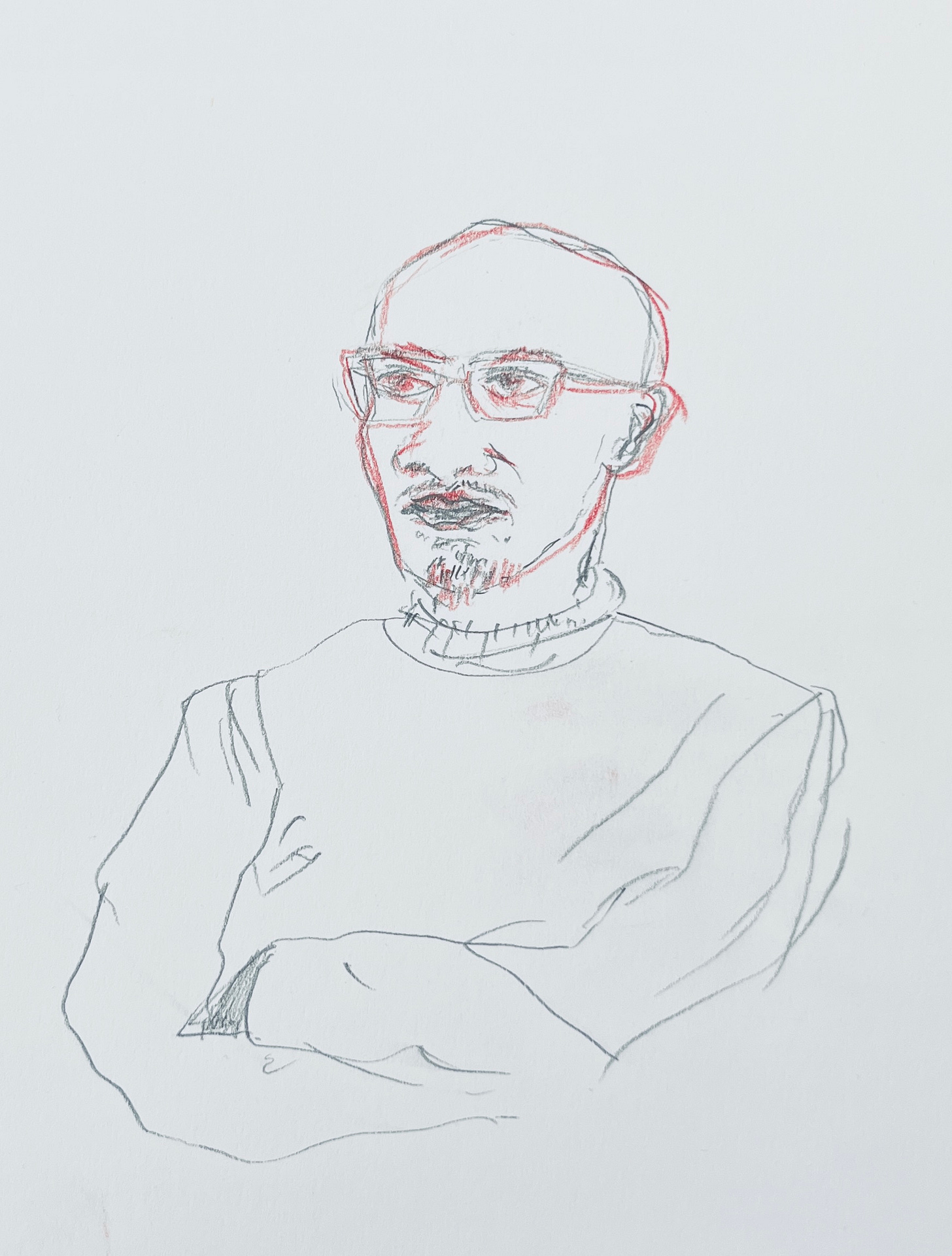

Early during this Spring break, because my son’s school was also closed, I took him on a road-trip. We went to visit an old friend. One night we watched “Drive My Car.” (Detail above.) My friend and I cooked and drank lots of wine and drew. See my midnight drawing of my beloved host below. During our visit, my son took part in a protest against ICE presence on campuses, visited an aquarium, and got some loot from Dubai chocolate.

Orbital’s going on my to-read list now. And Makkai’s ‘Livelihood’ substack. Sounds like a spring break well-spent :)

A lovely response to a fantastic novel! I loved reading this, my friend ...