The above image is a still from the film “Omerta” in which the actor Rajkumar Rao plays a terrorist. But this post is really about Ali Mir who appears in the images below.

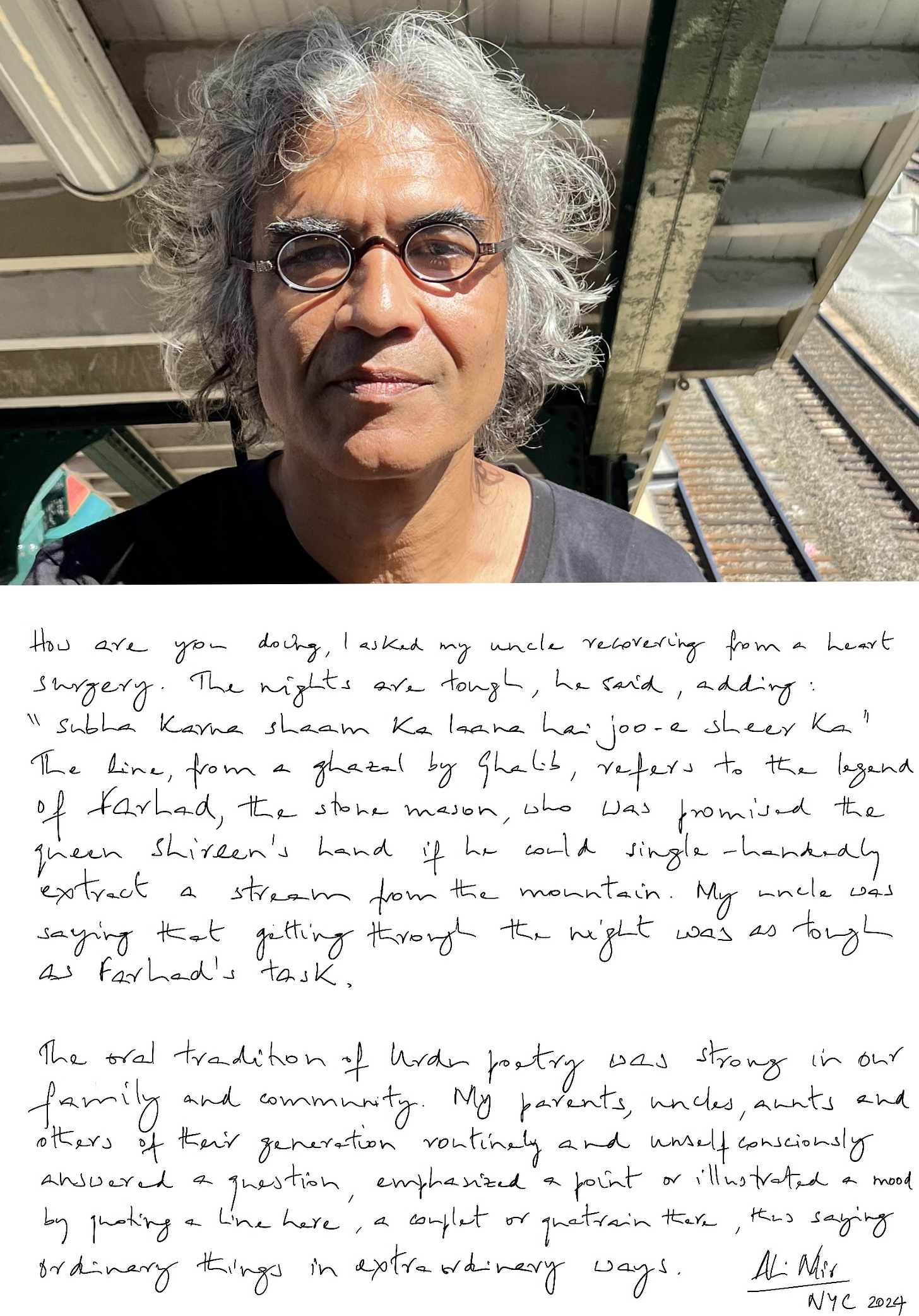

If you are a Muslim in India, trying to rent an apartment, your landlord might ask you, “Do you eat beef?” That is the stereotypical question for Muslims. But I have my own biases. I ask Muslims if they write poetry in Urdu. Now, this is a question that isn’t out of place with Ali Mir and his brother Raza Mir. I have seen Ali and Raza extemporaneously recite Urdu poems from different decades to delighted audiences. Recently, I asked Ali to tell me about the circulation of poetic idioms among his near and dear ones. He said that during their weekly family Zoom meeting, there are fifteen, twenty, even thirty couplets exchanged almost in passing. Let’s say someone shows a photograph they have found. One person will recite a couplet about vanished youth; another will spontaneously offer a rejoinder, etc. Please note the wonderful last line in what Ali offered me as a testimony.

But no one likes to stay imprisoned in stereotypes, even when they are mildly flattering. People, places, nations—these are all complex identities with all kinds of rich, mixed histories. Impossible to accept a bigot’s representation of a person or a community. Religion didn’t play too large a role in Ali’s upbringing in Hyderabad but leftism did. I begged him to write down for me a story he told from his childhood about receiving a gift—a red pencil—from the Soviet Union.

Those in the know will know that Ali has written film-scripts as well as lyrics for Hindi films. He is my native informant in that world. I interviewed Ali recently on a host of things. Here is what he had to say about the representation of Muslims in Hindi cinema:

During the early years of nation building, Indian cinema followed a formula in its depiction of minorities. Sikhs were typically jolly truck drivers, brave soldiers, or faithful friends. Christians were merry drunks and cabaret dancers (and occasionally the bad guy). Muslims were shown only in positive, albeit supporting, roles (except in the genre called the Muslim social, where most of the characters were Muslims who inhabited an imaginary world with an imagined history and a poetic idiom derived from an imagined understanding of Muslim/Islamicate culture). This wasn’t a formal requirement nor did the censor board insist on it; filmmakers were on board with the project.

Muslim characters were typically neighbors, best friends, tailors, shopkeepers, or the imam of the local masjid (seldom the protagonist or antagonist). Invariably, they were patriots. And they were all somehow, without exception, devout and practicing members of their faith, forever ready to roll out their prayer mat at a moment’s notice and ask for divine intervention on behalf of the hero or the nation. They also had to be marked in multiple ways. There was the name, of course. But just to help the audience along, Mohammad Miañ or Raheem Chacha also wore a skull cap, a taaweez (an amulet), and performatively greeted people with an elaborate salaam. Nearly all Muslim women covered their heads.

Though they were mostly marginal to the story, Muslim characters occasional played a significant role, such as in the blockbuster “Amar Akbar Anthony,” where three brothers of a Hindu family are separated in childhood (incidentally on August 15th, near a statue of Gandhi), and raised by a Hindu, a Muslim, and a Christian respectively. They are eventually united by their love for the woman who turns out to be their biological mother, a not-too-subtle stand-in for the – it must be noted, Hindu – nation (and to make sure the audience is hit on the head with this message, the mother is called Bharati, evoking Bharat, the name for India currently preferred by Hindu nationalists).

As communal tensions rose across the country, the secular character of Hindi cinema started to fray. “Tezaab”, a film of the late 80s, was the first ever movie with a Muslim villain, Lotiya Pathan. The early 90s saw the beginning of a significant phase of cinepatriotism, which shifted Hindi cinema’s traditional legacy of an inclusive nationalism decisively. “Roja,” “Mission Kashmir,” “Sarfarosh,” “Gadar,” “Fanaa” and a host of such films played upon the theme of the Muslim terrorist, typically bearing allegiance to Pakistan, who wants to tear the Indian nation apart. His counterpart is a loyal, patriotic, more-loyal-than-the-king Muslim who redeems his faith by proving his fidelity to the nation-state.

The heterosexual, patriarchal family is the model of the nation against which these two Muslims are juxtaposed. The former – the terrorist, the antinational – is intolerable and must be excised, eliminated, killed. The latter – the one who can only protest against discriminatory treatment by pleading to be included in the family – is necessary and must be sutured to the Hindu nation, partly to resolve the trauma of the history of Partition, partly to manage the nation’s anxiety at having to live with this Other in one’s midst.

In the 90s, the flood gates opened for mainstream Bollywood to embrace Muslim marginalization, normalize the trope of Muslim-as-terrorist, and turn movies into naked Islamophobic propaganda. Another more recent way of dealing with the Muslim “problem” is to write them out of the story altogether. Many current films and TV shows have no Muslim characters.

This short excerpt seems incomplete and out of place- on the Muslim question you point to Amitava! If you mention Hindi cinema, the Khans, the Salim-Javeds, are culpable in not shining any light on normal Muslim families or the problems of their ilk, only portraying Hindu lives in their movies. One can argue about the box office demands etc but the rich and famous Muslims of India hide behind a certain facade.

I have tons of Muslim friends and family and I love them.

There is so much to be said about this issue.

People’s lived experiences are getting sucked into political miasma created by Hindutva-vaadis.

Fascinating article on representation of Muslims in Indian film. I had no idea there was a time when Muslims were portrayed as neighbors or helpers in film. I’ve only ever seen the last 20 years of Hindi films in which every Muslim male character is slightly fanatical.