Exactly a week ago I got word that the journalist Sankarshan Thakur, a friend of my youth, had died that morning. When his cremation was to take place in Delhi that evening, I was looking at his emails and then I wrote a quick note about him. I was saying goodbye to him from this distance. We hadn’t been very close during recent years but there had been years, long ago, when we were the best of friends. I wrote to a mutual friend to ask how had Sankarshan been lately. She wrote back to say that till only a couple months ago, he had been texting her about his work. (“Sticking with commas like he stuck with his black coat,” our friend wrote and I recognized the truth in her wry remark.) I searched on my phone for any photos I had taken of Sankarshan. I found this one but I had no memory of when or why I had taken the picture. It is clear that my friend was trying out a new pair of glasses at the optician’s. We could see into the future. How far death would have been from our minds.

More than forty years ago, Sankarshan and I had seen each other every day. We both filled our diaries with bad poetry; also, we wrote journalism for Sankarshan’s father. Because we were so young, there were so many things we were doing for the first time in our lives. We would do these things together, and in that sense, we were witnesses to each other’s unfolding lives. On the day of Sankarshan’s death, a writer who is among my closest friends offered his condolences: “It’s hard to lose the people who in any sense co-authored our lives. They are never replaced.”

Here’s a memory: one night in the early nineteen eighties Sankarshan’s father came into the room where Sankarshan and I were writing. We were both smoking, of course. Wills Navy Cut. Instead of getting angry, Mr. Thakur only said, There is so much smoke here it is difficult for me to see anything. Mr. Thakur was himself a smoker; I thought his behavior was extremely cool. I would never have had the courage to light a cigarette in front of my parents. After the cancer was discovered earlier this year, I was told that Sankarshan had given up smoking. On the day he died, I wrote to my children saying that I had just received news about an old friend’s death and that I never wanted them to take up smoking.

The day after Sankarshan’s death, Pratik Sinha put out this tweet. See below. (I had met Pratik’s father in 2002 when I went to Gujarat to report on the riots. Mukul Sinha was a stellar human being and a great champion of human rights.)

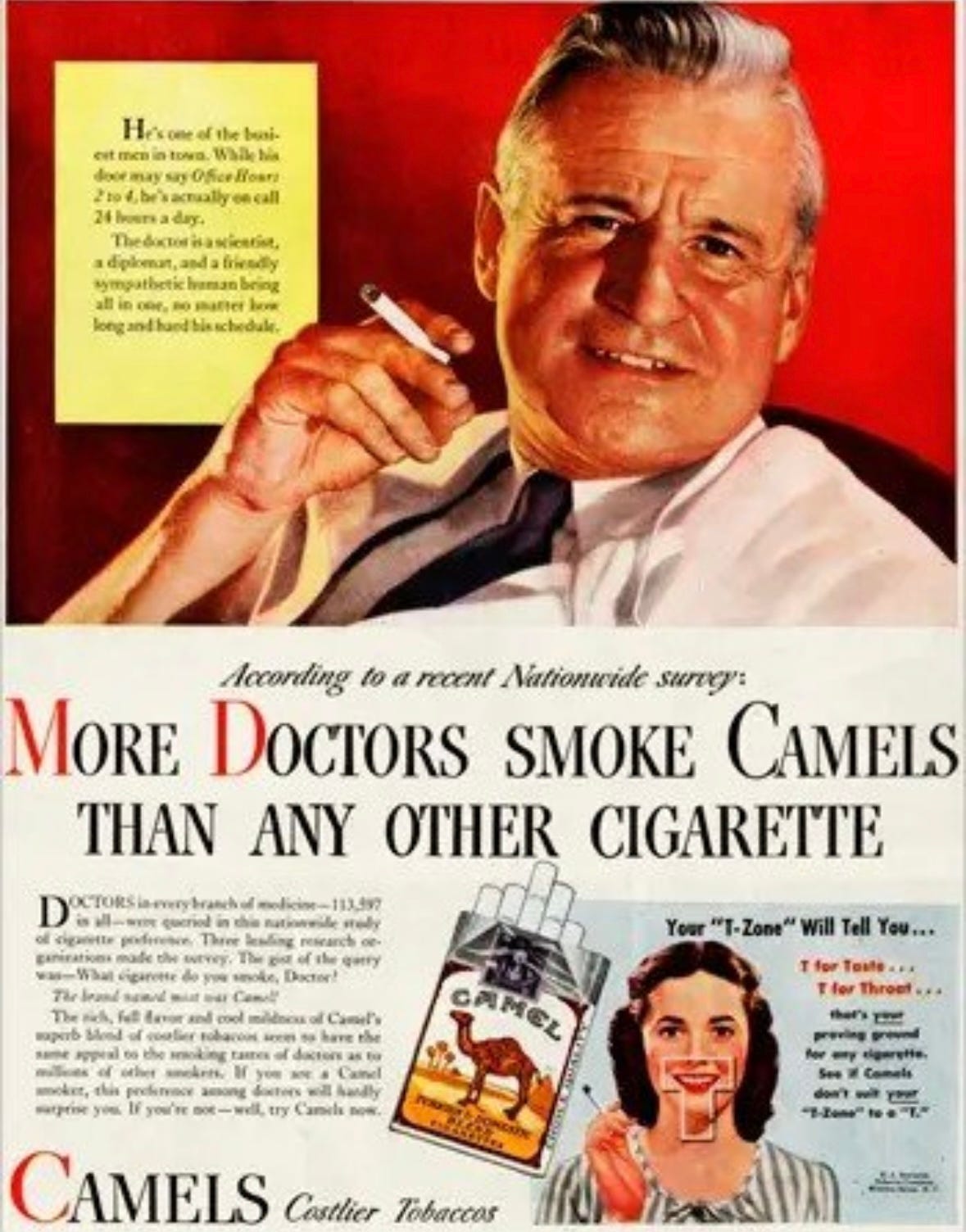

In the thread beneath Pratik’s tweet, someone had posted an old ad for Camel cigarettes:

A cursory search revealed that this was indeed an ad that RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company introduced into the market in 1946. This claim about doctors smoking their cigarettes “would be the mainstay of their advertising for the next six years.” The so-called survey had been carried out by the tobacco company’s own advertising agency; the agency’s employees collected their data from physicians at medical conferences and other venues after the doctors had been gifted free cartons of Camels. It is also true however that in the 1930s and 1940s, a majority of physicians in the US were smokers. So many ironies that mark our human existence!

I’m writing this post during the last days of my Hawthornden residency in Italy. There is a little bit of the feeling in me that I’m smoking my last cigarette.

Maybe this emotion is also evoked by the fact that each night before bed I have been reading a few pages from Simon Gray’s The Last Cigarette. This is the third in the four volumes of Gray’s marvelous Smoking Diaries. I like Gray’s diaries: his writing is brisk but reflective, also self-deprecating, and hilarious. This volume begins with his writing down in his diary “I intend to give up smoking.” This isn’t going to be easy. He thinks of everything crazy happening in the world. He writes: “When I ponder such matters, I consider it astonishing that I have decided to attempt to give up smoking.” A couple of days after Sankarshan’s death, I came across a passage in The Last Cigarette that follows a riff on the line “I am sorry for your loss.” Here it is: “The trouble with the dead is not that they are lost, and therefore might be found, but that they are beyond finding and are not therefore lost, they are absent to this world, in all the places that they were accustomed to be present in, and that you were accustomed to their being present in….”

Sankarshan had been absent from my life for a while but he was a presence in Indian journalism; his untimely death means that the sensibility he brought to national debates is now going to be absent. In my own life, his death is an intimation of mortality. Friends dying and the worry about my place in the line. And it is a reminder also of things that had receded into the past, all those memories, for example, of grasping at literary ambition, acts of rash and monumental stupidity, not to mention dreams of finding romantic love. In short, youth. In memory of that lost time, here is a postcard from more than forty years ago:

So happy you had saved that post card from forty years ago.

My heartfelt empathy. As we grow older, death is a shadowy presence at the edges of our beings. As friends of yesteryears and family members leave us, the absence they leave is a forever gaping loss, never to be found. As non-theists, we don't have the comfort of imagining a life hereafter, or rituals of departure that sooth our spirits. And all we can hope is that when our time comes, our departure will not be too difficult for ourselves and our loved ones.