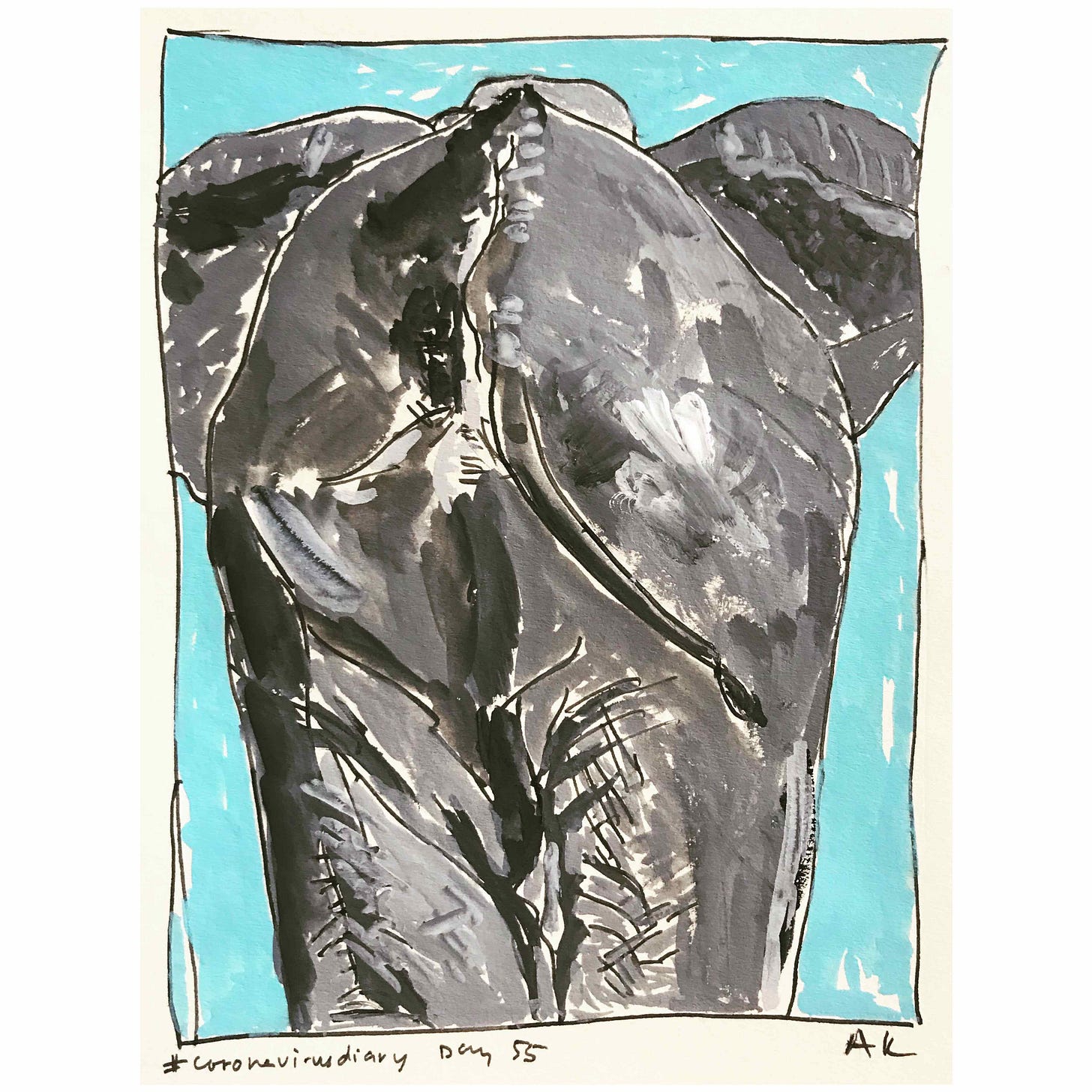

Elephant in the Room, Gouache on paper, 2020

I had titled my reading in NYC last night, “What did you do last week?” (A woman in the audience came up to me later on and said that she is a federal worker and she, too, had received that query from Musk.) But what I wanted to really title the talk was “Modi to Musk, Hold My Beer.” Or, maybe “Modi to Musk, Hold My Cow Urine.”

Talking of cow urine, I saw this little piece of news this morning. Please read it and then you can proceed to the text I read out at the Performance Space. (Thank you for the invite, Sarah Schulman!)

When I’m interviewed I often say that after my children have left for school, I make coffee and go up to my study and write for a while before heading out to the college where I teach. This is not entirely inaccurate. But on days when I don’t have anything pressing to write (rather, when I have a pressing desire to write but nothing appears as an obvious subject) I sometimes look over the pages of my old journals. Today I opened a journal, its spine cracked, to the page that has a faded yellow post-it sticking out of it: on top of the page, there is the word “epigraph” and below is a quote attributed to Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground: “…an intelligent man cannot turn himself into anything, only a fool can make anything he wants of himself.”

Did I see myself as an intelligent man because I had not by then turned myself into anything? I hadn’t written a novel yet and, in fact, I suspect that I was searching for an epigraph for what would eventually become my first book of fiction. I turn the page and see that there is a horoscope pasted there from Thursday, 19 June 2003: “Start clearing the decks. Don’t wait for a reason; good or bad. Just do what you know you have to and deal with what you’ve been putting off.” On the opposite page is a note I have made from listening to the radio. On NPR on June 22, 2003, I heard that an Iraqi newspaper whose name translates as ‘The Clock’ printed rumors about the American occupation: that the Americans had been burning Iraqi currency; that the Israelis had been buying real estate in Iraq, the way they had done in Palestine; that Saddam Hussein was in with the Americans and now living in the White House; and that American soldiers had been distributing porn to Iraqi schoolgirls. That last detail rings a bell. I’m certain I put it in the novel I was then writing but would not publish for a few more years.

I turn the page. Another horoscope. A torn strip of newsprint, this one from Toronto Star, July 3, 2003 pasted below the cartoon from the New Yorker. It says: “Financial objectives and career aspirations are changing. After almost nine years of private struggle or missed opportunities, a powerful wave of ambition and focus is now due.” How I must have wanted—waited and wanted—my first novel to be published.

I’m tempted to go on turning the pages. I don’t want to. There are two shelves full of these notebooks and journals. Who has the time? But really, just one more page. I turn to the back and the journal opens to a page where I have put a post-card. I recognize it. It is from a woman I once knew; I don’t want to read it. Another page then. Here I have pasted a print-out of an email from Hanif Kureishi: “Glad all’s well. When are you going to write a novel? How’s the baby? Love, H.” I look up to check the date. 14 September 2003. The baby was two months old. So many years have passed; that baby is now about to finish college and she will be stopping by in a bit to pick up her car that she had left here yesterday for her mom.

My first novel didn’t come out until 2007; I published other books in between and then I published another novel in 2018. And then, two more. I had thought I would look at the journals, or just at one journal, and find an idea I wanted to explore today, maybe a concept for a story. On occasion, just an observation or a few things noted in a single paragraph will light a spark. In ten days, I am reading at the Performance Space in New York and I have an idea about what I want to do when I read there. I want to be able to say something about how we mark our chaotic days. Every day there is fresh outrage in the news and new calls to action.

If Musk and Trump get their way, your private data and vital services disappear while they get richer. Senate narrowly confirms Trump nominee Kash Patel for FBI director. “What did you do last week?” Fired: Joint Chiefs Chairman, Top Navy Leader, Air Force Vice Chief, Service Judge Advocates General. U.S. votes against U.N. resolution condemning Russia for Ukraine war. DOGE is working on software that automates the firing of government workers.

This might be a new thing for a lot of us. It is. But it is also a bit familiar. During his last week in office in January 2017, President Barack Obama gave an interview to a book critic from The New York Times. Obama told the interviewer that his daughter Malia had read Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast and was captivated by the writer describing his goal of writing one true thing every day. (“All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”) When I read the interview, Trump had been president for two days, and I began keeping a daily journal, but instead of writing the truest sentence, I noted down a revealing lie. This practice of journaling gave rise to my novel A Time Outside This Time. The novel allowed me to process what was happening under Trump; it also allowed me to fashion what felt like a protest against the bad fiction called fake news.

In late 2017, a social psychologist at the University of Virginia name Bella DePaulo authored a comment piece analyzing Donald Trump’s lies. The Washington Post’s Fact Checker feature had been tracking every false and misleading claim made by Trump: in his first three years in office, Trump had made 16,241 false or misleading claims. DePaulo noted that with six daily lies on an average, Trump’s record on falsehood was higher than the national average in an earlier study she had done at the University of Virginia.

The U.S. President was lying every day but falsehoods I noted down could be from anywhere in the world. Here’s one from my country of birth, India: In the days prior to his retirement from the Rajasthan High Court, Justice Mahesh Chandra Sharma said that the cow should be declared the national animal of India because hundreds of millions of gods and goddesses lived in that sacred animal. The cow is the only creature, the judge opined, that takes in oxygen and also emits oxygen. He also extolled the virtues of cow urine.

In A Time Outside This Time, my narrator suggested that we must “slow-jam the news” because “all that is new will become normal with astonishing speed. You will go to visit your father and discover that he has pledged himself to the service of the Great Leader. Or you will visit your friend’s house and it will take a minute or more to realize that a meeting is under way and now everyone is looking at you with suspicion. You notice one fine day that all the signs on the road have changed. Your town has a new name. Dogs have grown fat on flesh torn from corpses lining the street where you grew up. The beautiful tree outside your window is dead, has been dead for some time, and has, in fact, just now burst into flames.”

I have stopped and am looking for one of the journals that I had maintained during that time. After finding it, I discover that my entries are fragmentary and present a puzzle; they cannot be consumed as readily as news and they give me space to think and remember. On December 12, 2019 I had copied down a poem by Kay Ryan believing that she must have written it about a phenomenon like the orange megalomaniac in office. The poem’s title is “The Elephant in the Room”:

Beneath the poem, is the following note from a place far away for some of you, but only an hour and a half away by car from India’s capital, Delhi. My journal entry says: “Muslim women in Meerut have said, ‘They took away our deen, we did not say anything. [Deen means religion.] But how can we stay silent if they take away our country from us?’”

Among the last pages in that journal is a note about the discussion with my editor about my putting Trump’s tweet from Nov 7, 2020 at the end of my novel. Trump’s tweet was “I WON THIS ELECTION, BY A LOT!” It received one million likes but Twitter had attached a warning saying “Official sources may not have called the race when this was Tweeted.” My point was that a presidency born in a lie about Barack Obama’s birthplace had ended on a lie in the words of Trump himself.

But now he is back, presiding over a high-tech kleptocracy, and in what I suspect is a futile gesture, I want to do be able to record accurately the feeling of what it means to be alive at this moment. A journal can be useful here. I say this because in the same journal that I have been quoting from earlier I find words that give me pause. I found them in an essay a friend had sent from the New Left Review (Nov Dec, 2019). The writer is Carlo Ginzburg and the critical line is this one: “A long time ago I suddenly realized that the country one belongs to is not, as the usual rhetoric goes, the one you love but the one you are ashamed of. Shame can be a stronger bond than love.”

Shame, not love. I’m certain I was thinking about India, not America, when Ginzburg’s words entered my consciousness. When I say this, what I feel along with the shame is a shadow of what is a kind of pride. You see, India is ahead of the United States. The problems you are experiencing today, we have already had to deal with last week. What did we do last week? We were dealing with this fakery and fuckery then. What we are burdened with today, you all are going to deal with tomorrow or maybe next week. (India is Number One!)

Prime Minister Modi’s slogan has been “India, Mother of Democracy.” What does this claim really mean? It means that while Americans for the past few weeks have become agitated about the dangers of a private company taking over the reins of government, in India by contrast, we have already been making rapid strides over the past several years with our own brand of crony capitalism that allows the privatization of airports, ports, mines, telecom industry, and even interference in defense deals. We can go back further in history. Hell, have you heard of the East India Company? That was a private enterprise that governed India and even owned the right to mint currency on behalf of the British Crown. Yes, we in India allowed a corporation to take over and rule us in 1757, long before the U.S. had even become a nation.

So much agitation among scientific minds during the confirmation hearings involving RFK Jr. for the position of the Health Secretary. What was RFK Jr’s fault? He asked the FDA to stop the rollout of the Covid vaccine. Big deal! In India, however, the Union Minister of State for Health and Family Welfare took the lead much earlier than RFK Jr., suggesting pro-actively that if people took the step of absorbing the sun’s rays for ten to fifteen minutes between 11 a.m. and 2.00 p.m. they would build the required immunity against coronavirus.

The billionaire owner of The Washington Post has given the directive that the paper will not carry opinion pieces opposing personal liberties and free markets. No need for such directives in India. We have a strong tradition of yellow journalism. During the Emergency, one opposition politician said, Indian journalists when asked to bend were ready to crawl. Now that politician’s party is in power. My friend Ravish Kumar calls Modi media “Godi media”: Godi media or lapdog media.

There are new and wholly valid concerns among Americans about the theft of data: will Musk and his minions steal the data stored in secure federal computers? Ha, I say, ha. Ha. There is so much America can learn from India. Under the BJP government, the answer to any serious inquiry about myriad routine questions, about matters as basic as our population, is to simply say “No data available.” There is no data, and therefore, no accounting.

As no data is available, I have become a collector of dreams. Maybe in America, too, I will do the same. Or you do it. My inspiration is Charlotte Beradt’s 1966 book, The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation. During my visits to India, I meet people, I take their picture and, next to these images, I then have them write something about their lives. In Mumbai, I spent an evening with a theater actor, Danish Hussein. Danish is Muslim. This is what he wrote about a recent nightmare: When I woke up in the middle of a dream, I found myself on a rooftop. This wasn’t the roof of my home. This roof was atop another house in the same posh gated community where I had my home. A gang of rioters carrying a list of Muslim homes was going around looking for Muslims to kill. My friends from the theater world were engaged in trying to save my life; however, they didn’t appear to be too perturbed. Now and then, they would watch Insta reels or YouTube videos and laugh loudly, but every time they received alerts on their phones about the movement of the gangs, they would point out the paths of escape and urge me to make my exit, telling me that I was safe. Filled with fear and exhaustion, in a country that is after all my own, I asked myself how much longer would it be possible for me to keep running.

The End

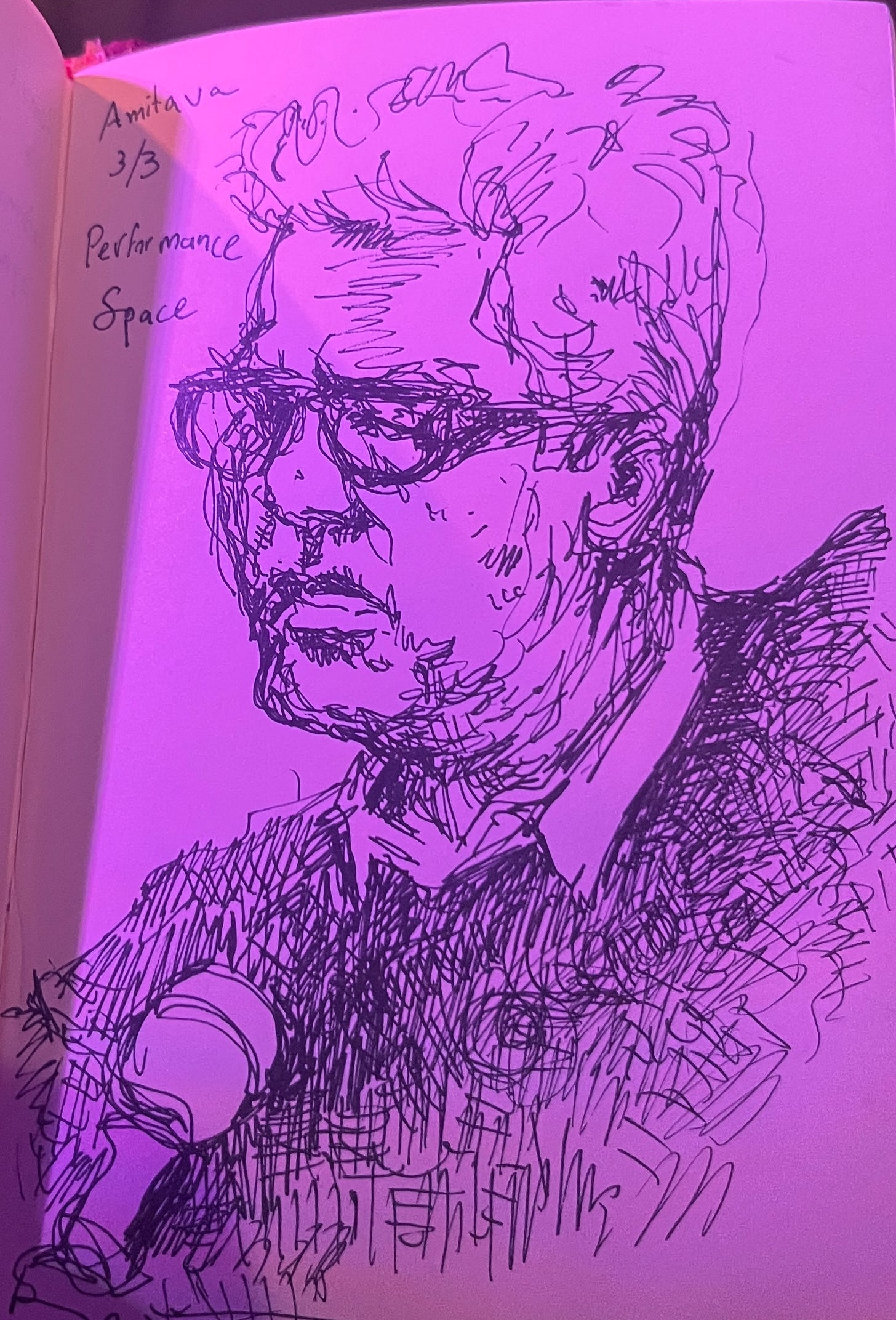

Also reading with me last night was the great Molly Crabapple. Here is her drawing of me from our event:

Yes, India is ahead of the United States in this racket, but the U.S. is catching up extremely fast and, unless something checks the speed and scope of the larceny occurring in our amazed faces, it will eclipse India soon. I write this with zero pride and in a state of terror.

And an extra "like" for Molly's drawing.