"How's Richard? How's Tonto? How's John? How's Chrissy? How's Judy? How's Mickey?"

My daughter is graduating from college

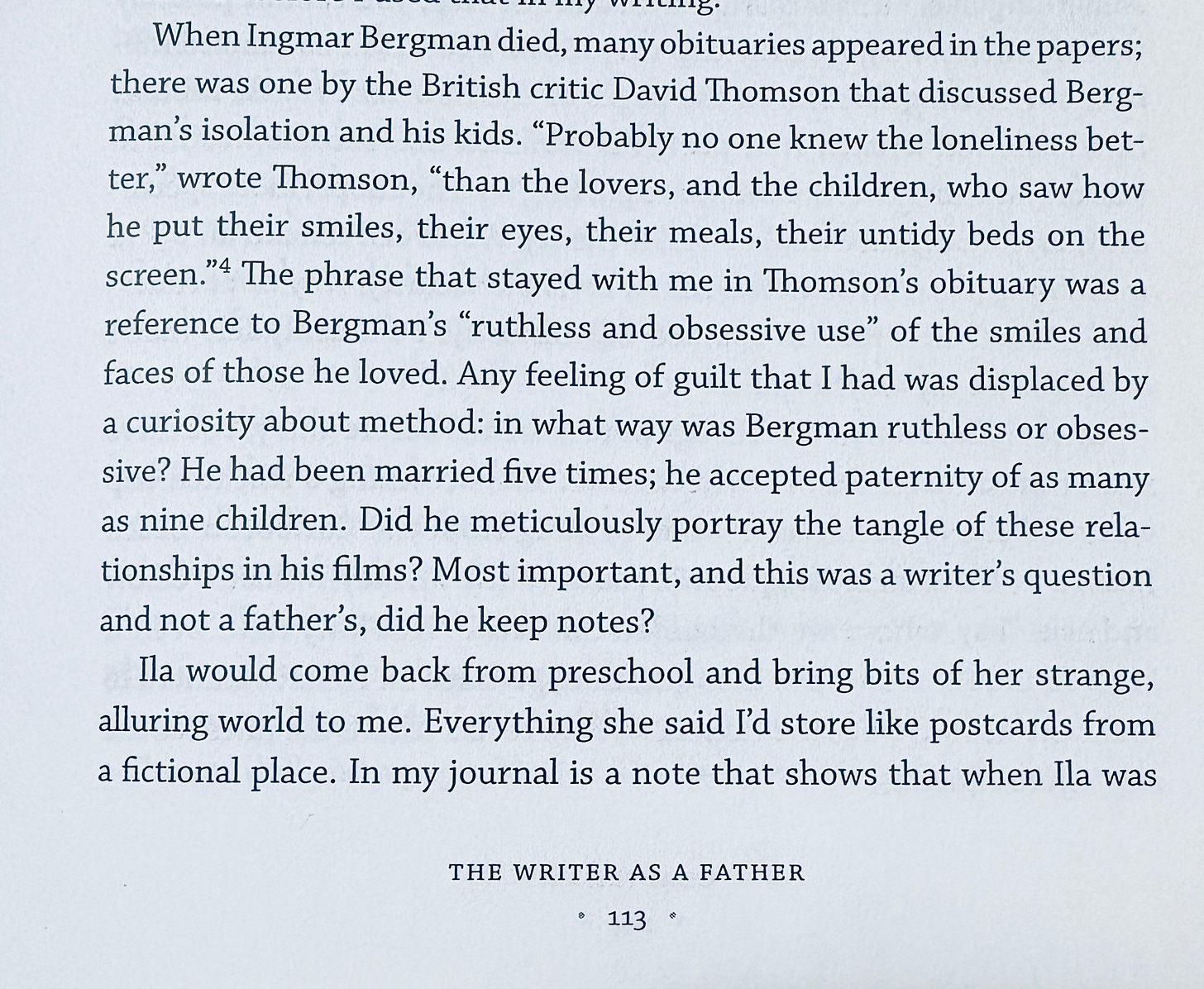

Ila on the Vassar Quad with her friends, May 2007

In a few hours, I will have the privilege of handing my daughter her diploma during Vassar College’s 161st commencement. The ceremony will be live-streamed, starting at 10 AM EST (7.30 PM IST).

The title of this post comes from a short-story by Grace Paley called “Friends.” A woman is dying from cancer and her friends have come to visit her; these are women-friends who are mothers of children who grew up together. As readers, we understand that this fact is the root of the friendship between the women, this fact like a bond of solidarity that they share. When the women come into her room, the visitors “solemn and embarrassed,” the one who is dying, her name is Selena, says to them, “O.K., first things first. Let’s talk about important things. How’s Richard? How’s Tonto? How’s John? How’s Chrissy? How’s Judy? How’s Mickey?”

She is talking about the kids.

Except that we already know from when the story started that something terrible had happened to Selena’s child. One night the police had called. “They said, Do you have a daughter named Abby?” (Yiyun Li’s devastating, scrupulously attentive opening in her latest nonfiction book: “There is no good way to say this—when the police arrive, they inevitably preface the bad news with that sentence, as though their presence had not been ominous enough.”)

Except that Selena remembers it just a bit differently, in the sense that when her friends arrive, she points to the dead child’s portrait on the wall and wanting to put them at ease says, “Life, after all, has not been an unrelieved horror—you know, I did have many wonderful years with her.”

Each year when commencement comes around, I’m happy for my students, happy that they have made it so far, and because of the relief and pride, I find tears spilling out when I congratulate them and their parents. I talk to one and I search for the others who are also graduating. In my heart, I’m saying “How’s Richard? How’s Tonto? How’s John? How’s Chrissy? How’s Judy? How’s Mickey?”

Many years ago, back when Ila was probably five or six, I was asked to contribute to a volume of essays by writers who were dads with daughters. The volume was titled What I Would Tell Her. (Another contributor to the volume was the writer Thomas Beller, incidentally a Vassar alum whose own daughter will join the college this coming Fall.) Like Selena in the Paley story, I wanted very badly to say in my essay that life hadn’t been an unrelieved horror—on the contrary, everything sweet or tender reminded me of my little child. Not just another child on street in a city where I was a stranger, a child shouting out Dad! Dad!, but even a bird calling in an overhead branch, ku-hu, ku-hu.

I remember being in a small town in Bihar, Bettiah, a couple of years after Ila had been born. This was late at night during a power-cut. In the front-yard of a house where I had come to conduct an interview with a man who was a childhood friend of the actor Manoj Bajpayee, two young servants were busy with a black cow that was about to give birth. Lanterns swinging in their hands, the youths explained that the last time one of the cows had given birth, it had been in the middle of the night. No one was around to take care of the calf. In the crowded stall, the mother had accidentally trampled her newborn to death. As I watched, fifteen minutes later, the calf arrived, its legs thin and crooked as a child’s drawing. I could think only of Ila as I gazed at the lovely little animal in front of me: Ila was also the child whose drawings had given me a way to look at the newborn animal that night.

Ila in London with Graeme, 2022.

When I was writing my essay for What I Would Tell Her, Ila was just learning to write words. Now, however, she is a writer in her own right. The fact that we are both writers, father and daughter, casts a new light on something I had written in that essay: I had informed the reader that I kept notes about everything odd or interesting my child was saying. When Ila was two, and my wife was nursing her, Ila turned away from one breast to the other, saying “This one not working.” The next line in my essay reads: “I remember asking myself how long it would be before I used that in my writing.”

The above essay from which I have been quoting (also reprinted in my own collection Lunch with a Bigot) has the following paragraph that I’d like you to read:

I have cited myself at length because I want to tell you that there has been a change —that I’m entirely rid of my guilt now. This is because I have just finished reading Ila’s senior thesis—her prose collection—and I see that she, too, has been taking notes and been rather ruthless in her use of details from my life. What I’m saying is that we are now even.

Here, for instance, is Evidence #1 from the long piece of fiction in Ila’s thesis: “… I told him my parents got married when their two countries were fighting a war. My dad was born in India, my mom was born in Pakistan. When I told people this story, it was usually around this moment that the image of Cyril Radcliffe came to mind. I would imagine this British lawyer—a man who had never before been east of Paris—tasked with partitioning the subcontinent in five weeks, using only a pencil and out-of-date maps.” Even when there is no resemblance to anything that actually occurred, I feel that a kind of emotional truth has been grasped. I’m trying to be as honest as I can, and so to provide a different kind of example, here is Evidence #2 from the same piece of fiction: “I thought about that summer—up in the Adirondacks at field hockey camp. Two weeks of wandering in the mountains, feeling completely alone and also excited to be away from home, even though I ate lunch with Rebecca, our coach, every day, because Grace Raffaele told me that I could not sit with her and the other girls because I did not shave my legs. I did not know how to. I thought about how, on the day he picked me up, I told my dad about it, and even though I cried and begged him not to, he got out of the car and went up to Grace as she was waiting to get picked up herself. Full of anger, digging my turquoise hockey stick into her chest, he told Grace that he would break her knees if she made my life difficult ever again.” I have tried very hard over the past twenty-odd years to consistently produce texts that are hybrid and that also mix genres. There is something boring about not challenging form. Which brings me to Evidence #3, my final example. Ila’s thesis boldly evades convention. It pitches an interesting mix of nonfiction and fiction. The introductory piece “How Will You Begin?” is made up of sourced nonfiction (people responding to a survey about campus life, especially at Vassar). I recognize an answer quoted in that introduction: “There was this kid in that class who had a disability—he had only one arm—and I asked him why he never wrote about that missing arm. He didn’t speak to me again.” As I said above, we are now even.

I’m proud of you, Ila. We are together in this business of writing literature, this sacred, worldly, difficult, exalted pursuit of truth. Keep working! Avoid mediocrity and, though this might be a challenge, do not care about applause.

P.S. Here are some of my favorite photos: one, two, three, four. There’s another one, the fifth, that I couldn’t locate on Instagram but I found I had a screengrab on my phone. I cannot remember how many years ago this was—certainly some years before Hua Hsu bagged his Pulitzer:

Amitava, I kinda hate you temporarily for writing this extremely good essay.

Also I love you permanently for writing these extremely good essays.

Congratulations to Ila and her writer father. My daughter Anjali, just turned thirty, told me teary-eyed when she was around four years old and I was on deadline for something or another and couldn't pay her the attention she wanted at that moment: "I don't want to have a writer mommy. I want a regaleer mommy like everyone else!" (She pronouced "regular" at that age in a way it rhymed with "cavalier".) Sounds like Ila is more than making the best of being a writer's daughter.