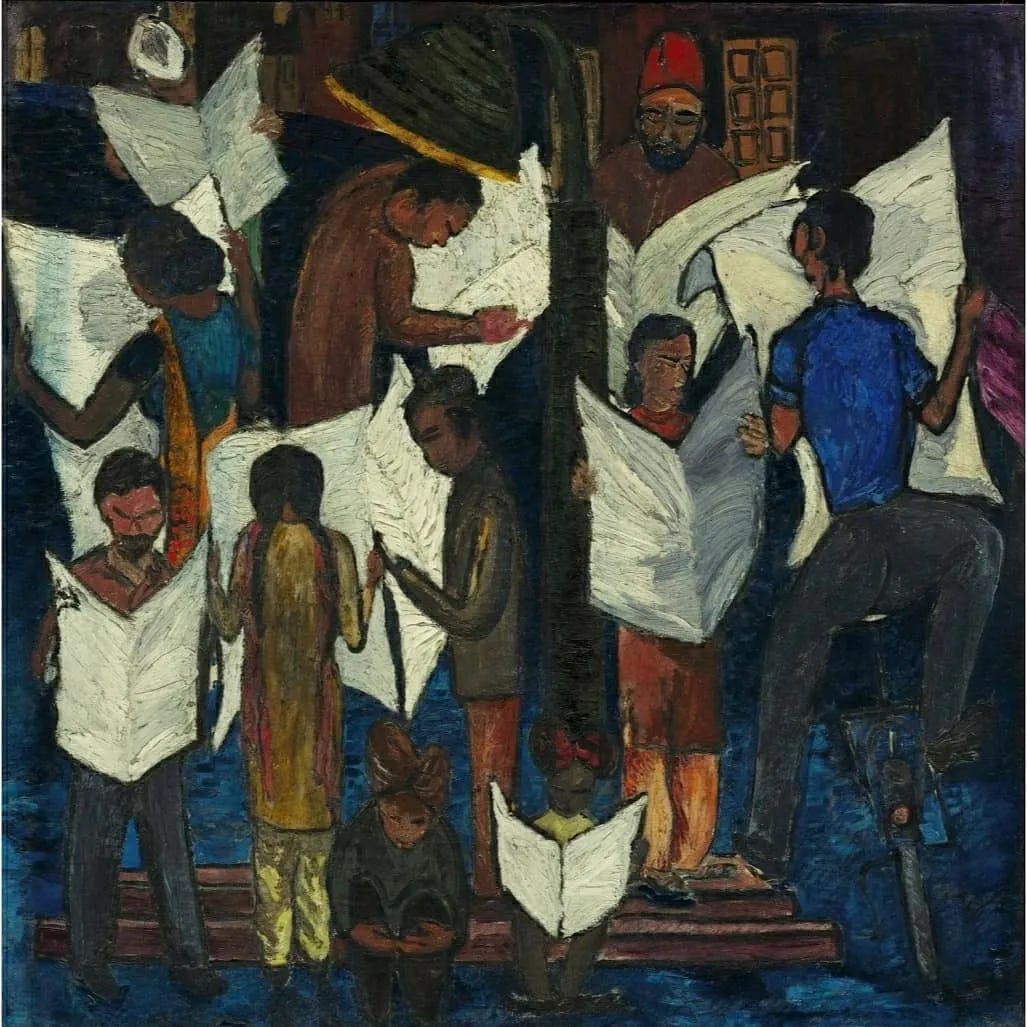

“I was in Delhi when Gandhiji was assassinated. As I walked home in the evening I saw a group of people huddled under a lamp post anxiously reading newspapers. The image followed me for a long time, till I painted it in 1948.”

Krishen Khanna, “News of Gandhiji’s Death,” 1948.

A couple of hours ago, I asked my friend Ranjit Hoskote to tell me about the feelings that are invoked in him when he looks at this famous painting. Ranjit is all sorts of excellent things: poet, translator, art historian, theorist, curator (and who the hell knows, maybe even a cricketer, falconer, figure skater, and a champion glass blower). He said that this painting is dear to him because it suggests the possibility of “solidarity of grief.” What we see is a public gathering of people absorbed by a singular tragedy. Gandhi, whether you agreed with him or not, had brought people together. Looking at the painting, one can imagine there exists a possibility of a space available for public discussion. “This couldn’t happen today,” Ranjit said. He was speaking from his home in Mumbai; I was sitting in the New York Public Library. Ranjit allowed that while people in India are engulfed in outrage fueled by WhatsApp forwards, so many other emotions somehow stand erased in the broader public domain—shame, guilt, a sense of pause. What is more readily in evidence are extreme forces who are happy to brazenly own their extremism. That is the truth of the extreme right, erasing any notion of common humanity. And, added Ranjit, the liberal left appears trapped within sectarian communities, more worried about the semantic violence that appears to be enacted on their particular choices instead of coming together. People don’t see the larger picture. In Krishen Khanna’s painting, in contrast, people are coming together because this larger picture is present. The figures, quite literally, occupy the frame of the larger picture.

Ranjit and I went on to discuss other things, including Atul Dodiya’s project on “the artist of nonviolence,” Kumar Gandharva’s bhajans, and Ranjit’s own eco-poetics. I want to remain for a moment or longer with the observations above about Khanna’s paintings. In the face of the fresh horrors each day, how to introduce pause? How to stop time? I’m quite fond of a quote from Maxine Hong Kingston that I have put in my book of drawings and diary entries coming out this month: “In a time of destruction, create something. A poem. A parade. A community. A school. A vow. A moral principle. One peaceful moment.” This quote gives me pause when I’m too quick to doubt the practice of writing.

What else is one to do? I admire people who put their bodies on the line, people who protest—I say this even while I sometimes find signing of petitions futile, or at least only performative. But, I tell myself, if I write down what I’m witnessing what is happening out in the world I’m creating a necessary record. [P.S. This post from today, which I just read, has been written by Catherine Lacey. This is a thoughtful record of this moment.] When I was writing The Yellow Book, my friend Ian Jack hadn’t died. In London, we had gone on walks together. Hanif Kureishi hadn’t yet fallen down and been left paralyzed. Just a few months earlier, Hanif had met with my class. He hadn’t yet dictated those sparkling reflections on illness and on writing that have inspired people all over the world. My father was still alive. The world turns and turns, again and again; I’m happy that a diary can serve as a record of changes and also as a memorial to what once was. During these days of war, so immediate and devastating for many, so distant and therefore tolerable for so many more, I want to add my voice to those demanding a creasefire, of course, even as I go on collecting and attempting to present in the public sphere other voices. For example, these words, full of gallows humor and hope, by the Palestinian poet Jehan Bseiso:

Habeebi, I thought you lost my number, turns out you lost your legs,

On the way to the hospital from Khan Younis to Jabaliya to Rafah.

The border is closed, but my heart, tunnels.

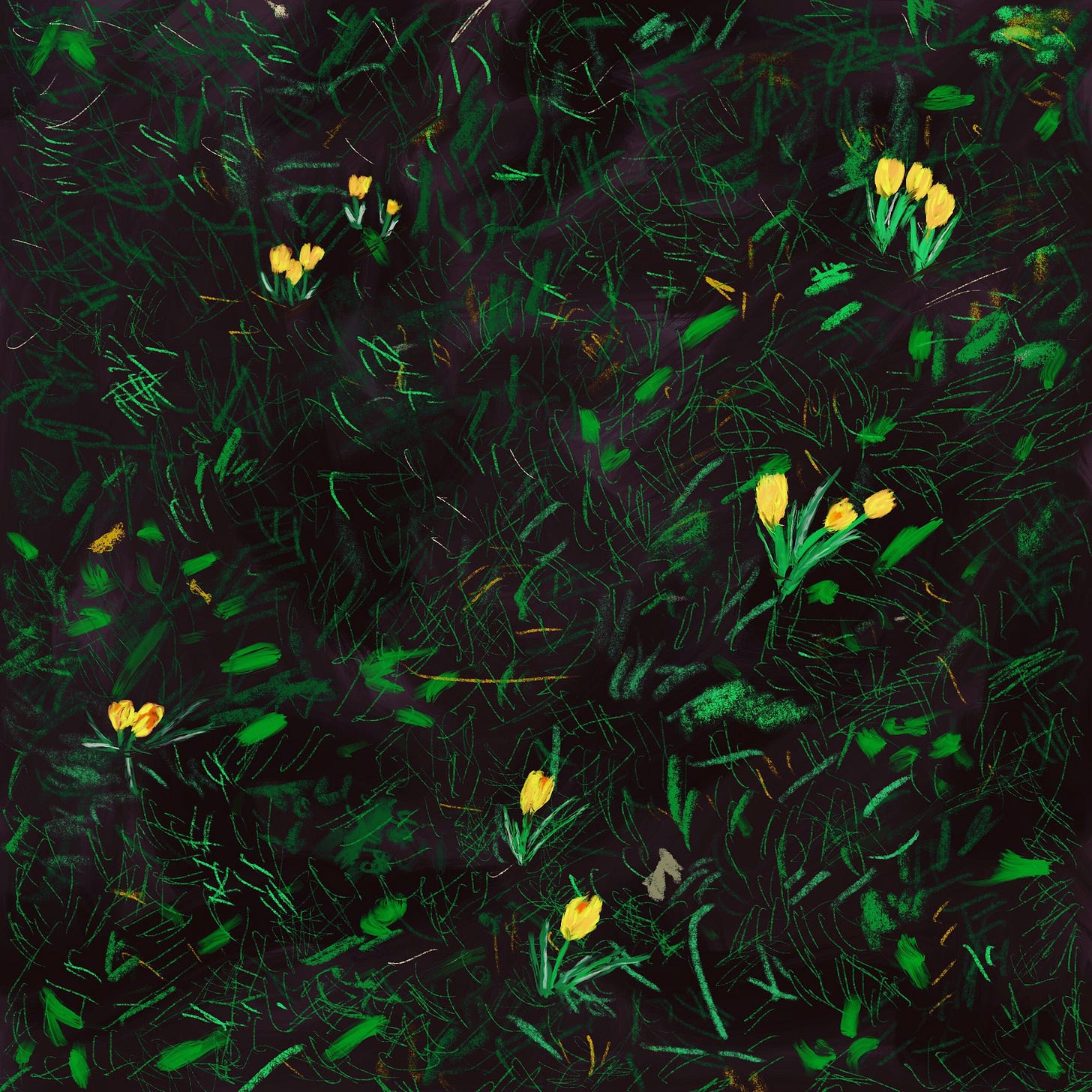

“Crocuses,” from the chapter “You Must Believe in Spring,” in The Yellow Book

Some beautifully expressed truths there, sirji.

I saved this to read and just now got back to it. I'm so glad I did. The idea that war is immediate for some and distant to others has always haunted me. The words and the picture struck home.