Over the last few days, I have watched nine documentaries that are a part of a series called “Election Diaries,” reports from the Indian general elections of 2024. We learn from these documentaries that opposition candidates pitched these elections as decisive, a struggle for survival of the idea of democracy in India. If the BJP wins again, the candidates tell their constituents, our Constitution will be in danger. As it turned out, the BJP won but it couldn’t secure a majority on its own; Modi returned for a third term only with the support of regional parties.

The above screenshot is from the documentary “Ruke Na Jo” (Unstoppable) by Prateek Shekhar. It offers an excellent account of the election campaign in Bihar of Sandeep Saurav, a communist who was the opposition’s candidate in Nalanda. Saurav got a Ph.D. in Hindi from JNU; he was a student leader and is currently a member of the Bihar legislative assembly. He is 38 years old. Shekhar’s film about Saurav’s campaign is a valuable document because it shows you how a campaign with minimum financial resources (collecting twenty rupees as a donation from each household) is carried out against a behemoth like the BJP with huge backing of rich corporations. The camera finds Saurav’s face addressing crowds on the streets and in small shops, his skin glistening with sweat. More than once, there is a power outage and the screen is plunged into darkness. We are in a poor land in terrible heat. The candidate is campaigning among mud houses. All this in itself becomes an argument for bringing change. But I liked the documentary even more for the simple strength and the sweet optimism of the candidate. When news comes in that he has lost the elections, Saurav says that he hadn’t stepped into politics with a desire for power. That was never the point. An important lesson this: politics are a platform for struggle.

Pankaj Rishi Kumar’s “Gola Dreams” is a report not just from the heart of the heartland (Lakhimpur Kheri district in Uttar Pradesh) but also, it felt sometimes, from the depths of despair felt by India’s most marginalized. While reporting on the electoral battle in 2024, the film-maker finds his able sutradhars, the people who articulate their reality, in the form of a Dalit journalist and a Muslim e-rickshaw driver. Add to this Kumar’s expertise with story-telling and the control of narrative. Films, as a visual medium, rely on faces. And I thought even the face of an unnamed daily-wage laborer was unforgettable. You can see him above in my screenshot. He calmly explains how he earns a pittance (300 rupees daily) and what he will need to do if a child falls sick (get money from a moneylender at high interest). His resignation is also a form of desperate resolve. He raises questions for which there is no answer, and for that alone this is a film worth watching.

Alishan Jafri and Omair Farooq collaborate on a documentary reporting from Hyderabad on the campaign of Asaduddin Owaisi. “Crescent in the Saffron Sky” begins with a chilling recitation of the demeaning slogans and threats popular against Muslims in recent years. For example: “Jab mulle kaate jayenge, woh Ram Ram chilayenge” (When Muslims will be slaughtered, they will shout the name of Ram). An invaluable reminder that the 2024 elections and the fight against the BJP was a call to restore secularism in India. Or at least to point out how communal politics was the pivot on which the ruling party had made its appeal for majoritarian support. (In fact, perhaps all the films in the series have included Modi’s infamous campaign speech in Rajasthan. That was where he called Muslims “infiltrators” and warned that his electoral opponents would snatch the wedding gold of Hindu women and give it away to Muslims. Whatever other talents the prime minister might have, there can’t be a bigger one than that of being a champion dog-whistler.) In this film we witness Owaisi, who is often portrayed in mainstream Indian media only as a polarizing figure, again and again asking voters to “defeat the communal forces.” At one rally, he also plays the tape of a poor 70-year-old Muslim man who makes a tearful statement: “My ancestors are buried here. My children will also get buried here. I won’t leave this land. They tell us to go to Pakistan. I’m not a Pakistani, I am Indian! …” When the old man’s words are being played at the rally, the camera passes over the bowed heads and faces in the crowd. There is a palpable sense of empathy on those faces. Owaisi later tells the film-makers: “That old man, when he started speaking I’m sure every Indian Muslim was connecting with each and every word that was coming out of that old man’s mouth. Every word.”

Let me now discuss another documentary bringing a report from the south of the Vindhayas. In “Sangama” (Coming Together), Sunanda Bhat offers a reassuring account of citizen activism during the 2024 elections in the state of Karnataka. Using the cry of “Eddelu” (Kannada for “wake-up”), the film shows mobilization drives undertaken to fight against majoritarianism. One of the activists explains why he is motivated to organize his community against hate: “If someone disturbs a beehive, can one keep quiet?” Many of the films in this series underline not only the fact that elections are truly a mass affair in India but also that so many small, unnoticed lives contribute to the defense of democracy. “Sangama” is, therefore, a statement about a collective gathering for our rights. I should add that having already watched “Ruke Na Jo” from my home-state Bihar, I couldn’t but notice how much cleaner and swankier the settings were in Karnataka—citizen activism as more of a middle-class or upper middle-class affair. But Bhat has her eye on other classes too and above is a screen-shot of an exchange from the film presenting a demand by working-class women.

“State of Hope” by Anjali Monteiro and K.P. Jayasankar starts with lush passages revealing the landscape of Kerala’s Pathanamthitta district where the Left had fielded Dr. T.M. Thomas Isaac as their candidate. (That is Dr. Thomas Isaac smiling, above, on the side of his election van.) While a few of the documentaries in the “Election Diaries” series were overly invested in talking heads, Monteiro and Jayasankar take pains to use the medium to show the texture of places and people even when they are presenting us the spoken testimonies (or, as is inevitable when talking to Marxists, analyses). I enjoyed watching “State of Hope” because, well, it presents hope: it does so in the ways in which Thomas Isaac, an economist and a former minister of finance, speaks lucidly of his constituents and their needs, and it does so also by displaying the ways in which the poor, particularly women, are empowered in different walks of life. The film, unabashedly supportive of the candidate, also reports the disappointing news that Thomas Isaac lost. He was not the choice of the voters and that’s the further challenge confronting “Election Diaries”: how to have such films reach the people who vote and become a factor in their decisions.

The above image is a screengrab from Namathu Chinnam (‘Our Symbol Is…’), a documentary set in the state of Tamil Nadu. (“Election Diaries” pays strategic importance to southern states, which are the battlegrounds where the chariot of the BJP runs aground. In fact, the film’s directors, Greeshma Kuthar and Dr. Manju Priya K., cheekily describe Tamil Nadu as “the far-flung state of anti-nationals.”) In a manner similar to “State of Hope,” this documentary also offers rich visual material—the panoramic everyday, the lives and conditions of the overlooked voters—while scrupulously attending to the powerful and affecting ways in which people speak about life and its inequity. At another level, the film is also a meditation on symbols—or, more specifically, on how dissent or critique is contained when turned into mere symbols. For instance, the statues of B.R. Ambedkar, often put in cages for their protection, even while his ideas, as the film-makers put it, “remain inconvenient for those in power.” The right uses cultural symbolism to consolidate its power—how is the left to revive or also create its own effective symbols?

Amit Mahanti’s “Inside Out” is the election diary that reports on regional parties in Meghalaya contesting for the Shillong parliamentary constituency. Framed as a personal essay, the film broaches the binaries that govern social life in Meghalaya: locals/nonlocals, tribespeople/plainspeople, etc. In doing this, the film foregrounds a theme that is of concern in other films too—who is an outsider? Who belongs and can claim true citizenship—and who must be cast beyond the pale? The election was ultimately won by the VPP, the new party that was campaigning on a partisan slogan aggressively centered on land, tribal identity, and cultural preservation. The losing candidate from the NPP argued for a more inclusive, cosmopolitan, and perhaps more elitist, identity but her platform was soundly rejected by the people. “Inside Out” interested me because it again foregrounded the status of minorities. See screenshot above. We see that in the Shillong election “Hindu India” was reduced to a minority—and yet in its anxiety about the outsider, the election in Meghalaya seemed to offer a parallel to the BJP’s propaganda about outsiders in India. However, are they in any real sense parallels? Don’t the locals in Meghalaya have a legitimate concern—certainly more legitimate than the majority in the mainland, more than 80 percent Hindu, claiming to be threatened by the Muslim minority?

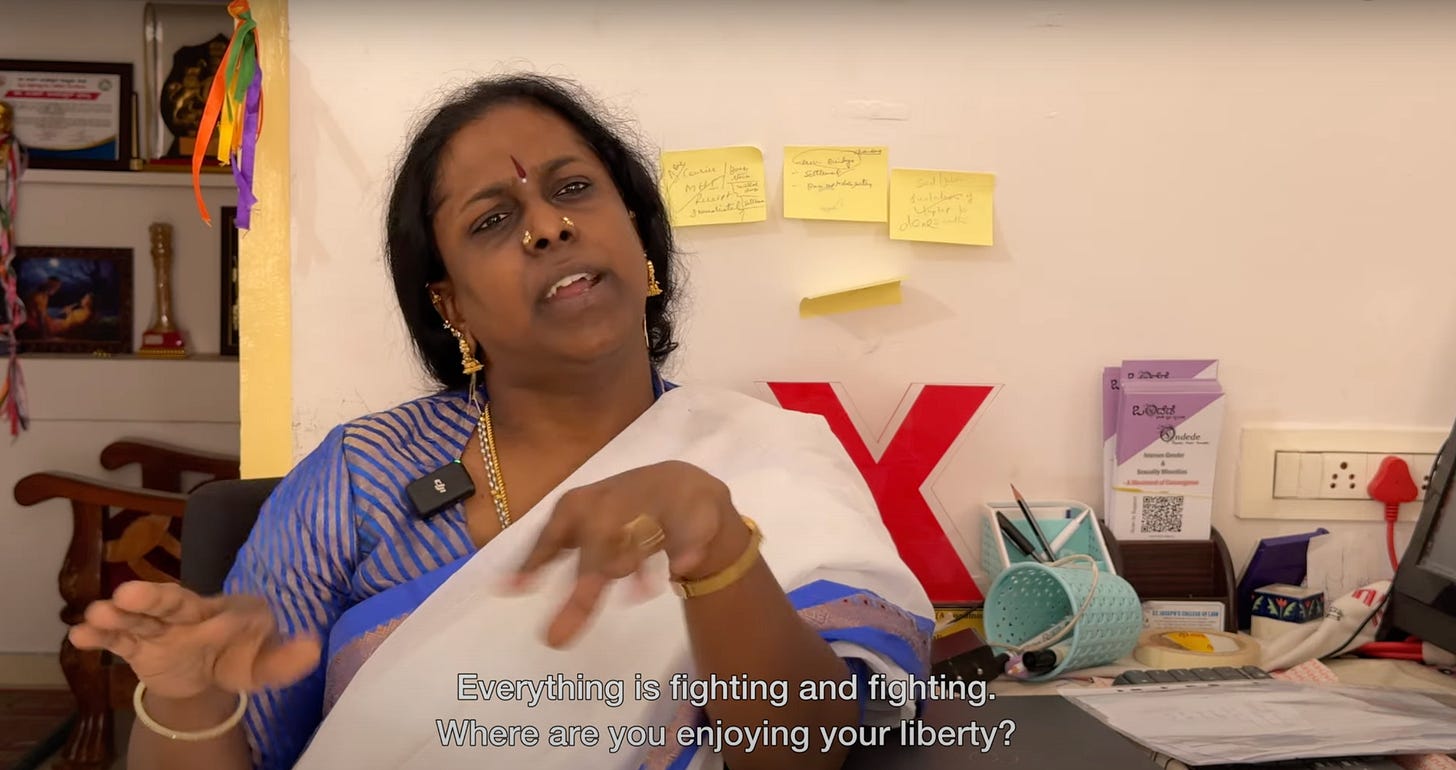

Talking of minorities, Avijit Mukul Kishore’s “The Miniscule Minority” brings us conversations between the film-maker and LGBTQ activists who consider the point that queer rights were not on the agenda of any of the political parties during the 2024 elections. The screengrab above is of transgender politician Dr. Akkai Padmashali who prefers the label of “minority” over “queer” because that gives them the chance to speak with and for other “voiceless communities,” including caste and class minorities. The film’s title comes from the Indian Supreme Court’s 2013 judgment that dismissed queer rights as “the so-called rights of a miniscule minority.” (This judgment was overturned in 2018.) In the absence of any party campaigning for queer rights, we are restricted to a handful of activists telling the film-maker about their experiences in the public sphere.

The first documentary that I watched in the “Election Diaries” was “Battle Royale” by Lalit Vachani. He is also one of the producers of this series and I have admired his earlier documentaries, not least the recent one about Umar Khalid. “Battle Royale” tells the story of fiery politician Mahua Moitra’s re-election campaign after the BJP had ejected her from Parliament for asking questions about crony capitalism. Moitra is a gutsy politician and doesn’t flinch from attacking the powerful. Vachani told me in an interview that he was drawn to the story by its “dramatic potential,” the redemptive arc of a female politician refusing to be shut up. The screengrab above is from a roadshow that Moitra participated in just before the elections. She won by a margin of 56,705 votes. I feel grateful and a tad envious of Vachani for his initiative in creating this series of films; they offer an opportunity for a public education in democracy.

Thank you sir

Sir, where can I find these documentaries?