A Train Is Approaching

Announcing a New Book

Aleph Book Company in India have published several of my books and in December this year they will be bringing out a new one. A short book in their excellent ‘Essential India’ series. The book will be sold in the Indian subcontinent. (Outside the subcontinent, this account of train journeys is part of a bigger, forthcoming book covering other forms of travel in the country across several years and countless interviews.)

My thanks to Aleph—in particular David Davidar. I’ll be participating on November 30 at a book event at Champaca Bookstore in Bengaluru and at Kunzum in Delhi GK II on December 2. More details to come.

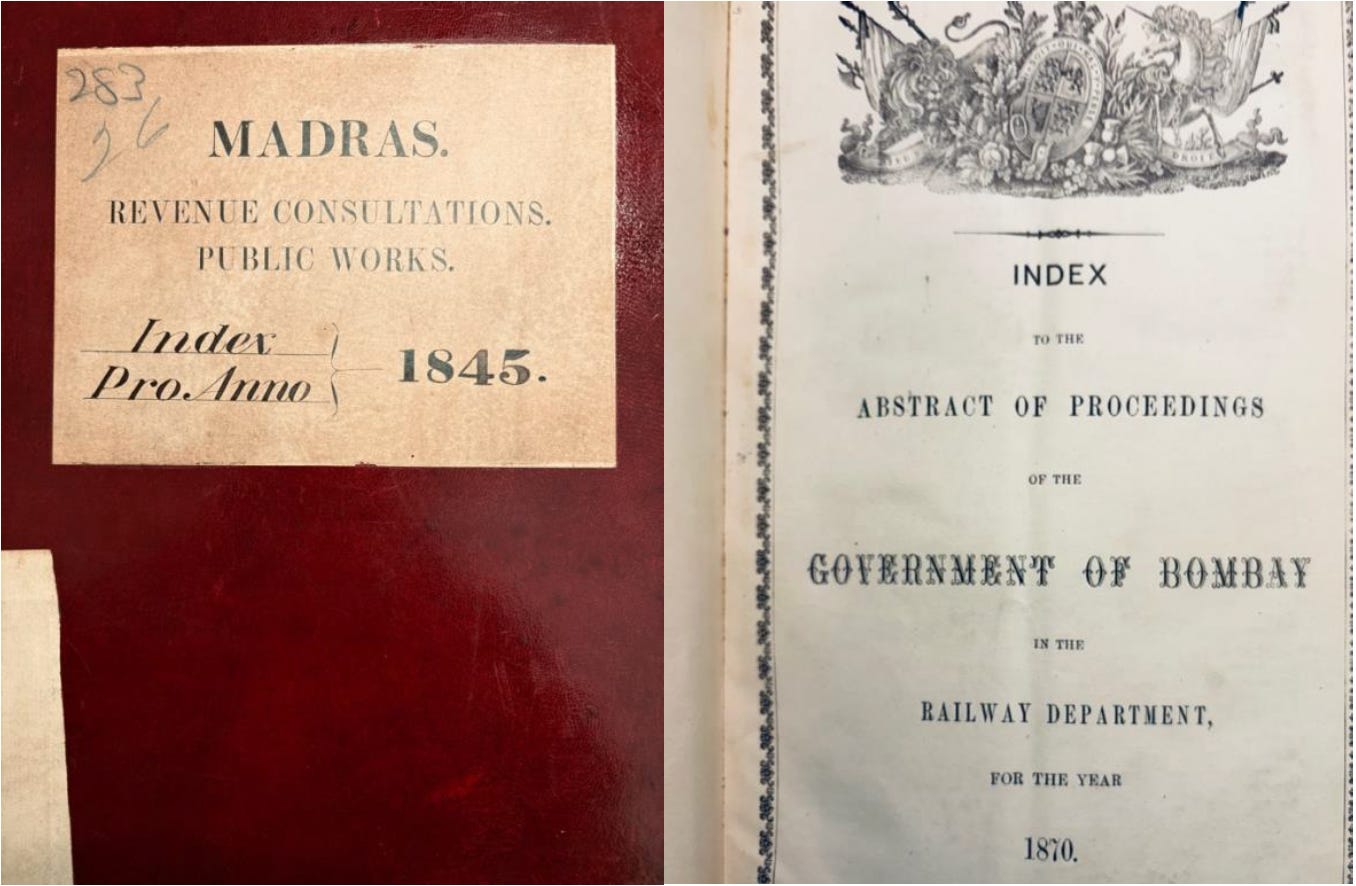

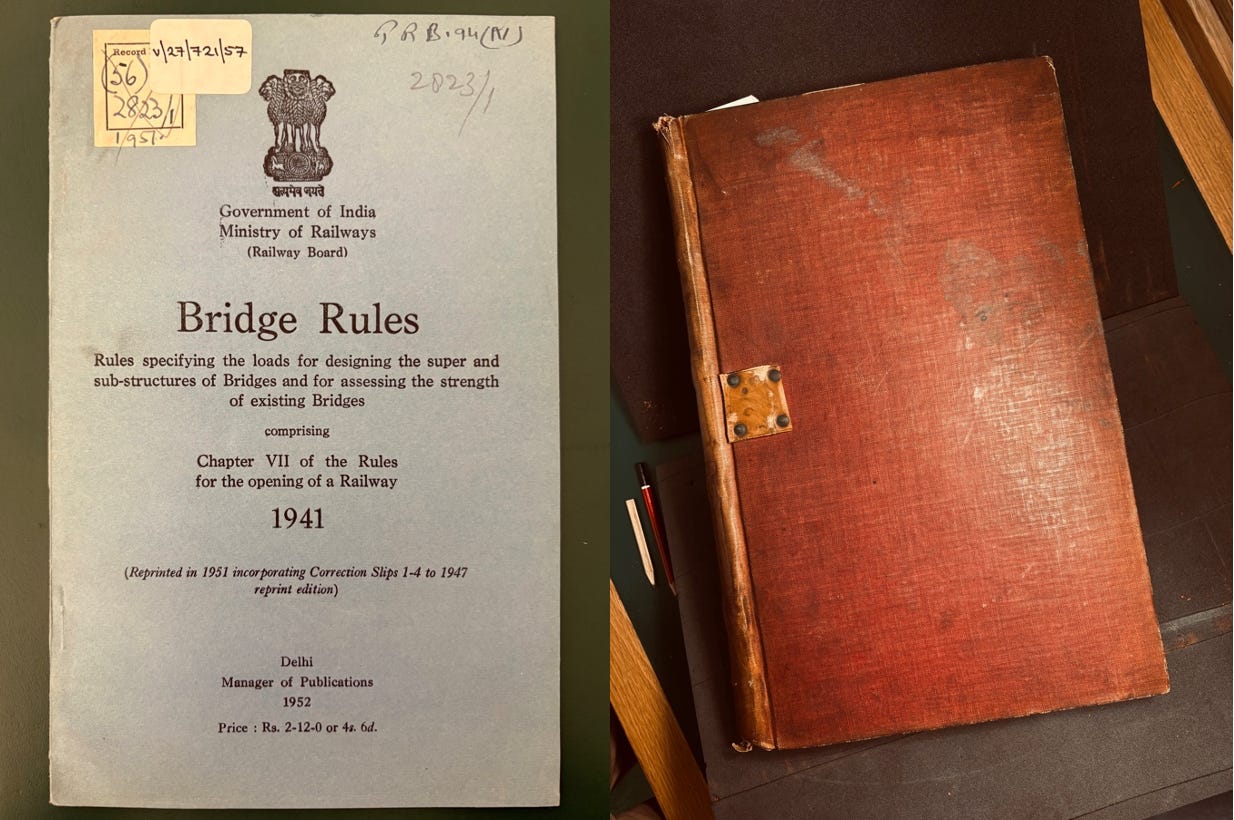

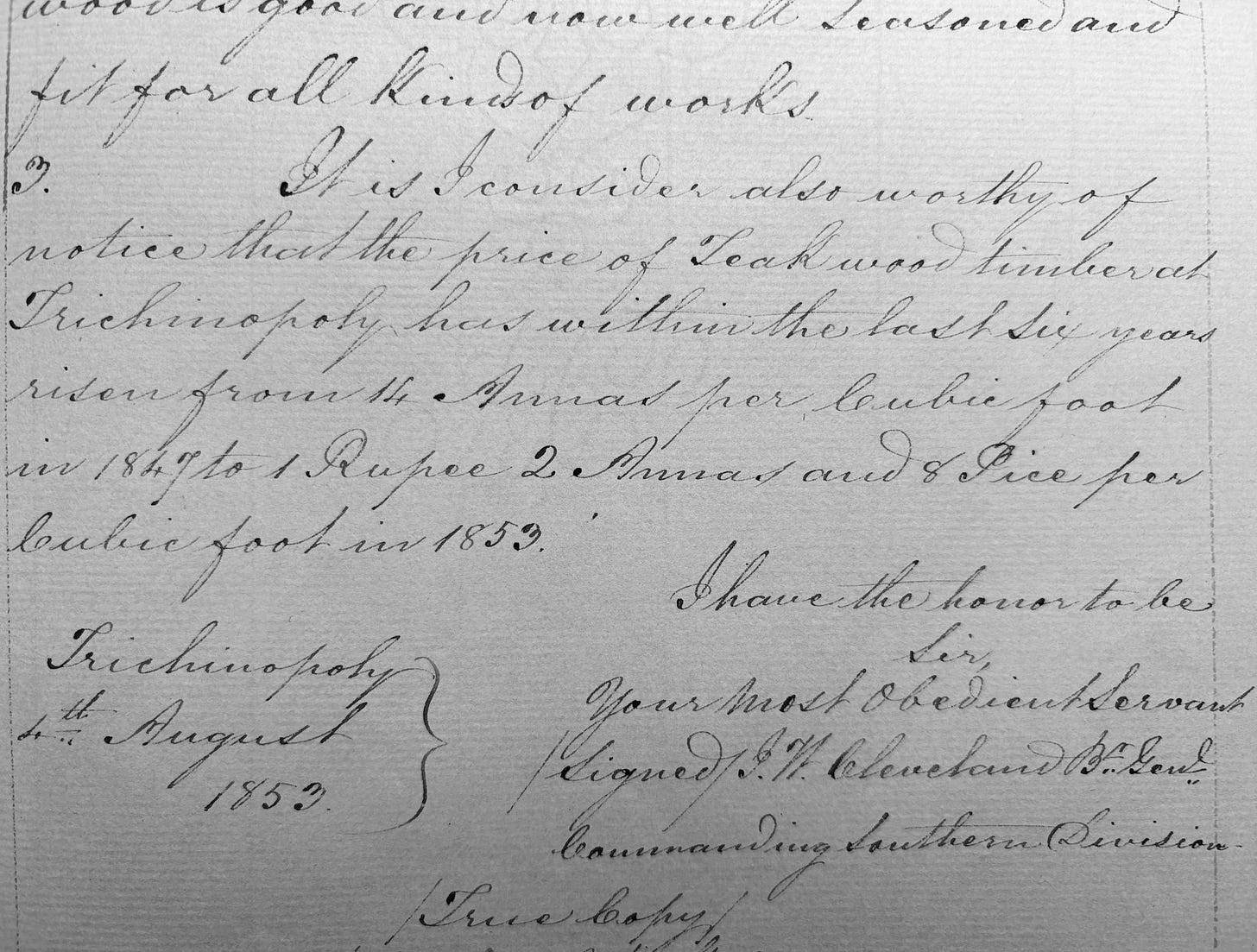

In this post, I want to tell you what it was like to look at the Public Works archive in the British Library about the railway in India. First, the rather naive or a beginner’s fascination with handling documents a century or a century and a half old. I wondered who had touched these pages last. What were the conditions under which they had been assembled. Second, the level of attention to detail required for the colonial rule to execute its design, to govern the land and exploit resources in the way that it did. In a carefully contained cursive hand, the careful documentation of expenses down to the last paise! (What did those curlicues express, and what did they repress? Such a fine handwriting, so much order! What does this neatness hide of the corruption and public pain?) Here, in a record about the construction of the railway from 4th August 1853: ‘It is I consider also worthy of notice that the price of Teakwood timbre at Trichinopoly has within the last six years risen from 14 Annas per cubic foot in 1847 to 1 Rupee 2 Annas and 8 Pice per cubic foot in 1853.’

The railway was being established to transport goods, say, cotton from the hinterland to the ports from where they would be taken to the mills in Manchester. Especially after the revolt of 1857, the laying down on lines and import of locomotives was seen as important for another reason: a quick way to transport British soldiers from one part of the colony to another. But as I sat day after day in that library in London, it delighted me to find little scraps of information about small places that had been familiar to me since my boyhood in Bihar. One afternoon, I came across a report of an investigation into a railway accident that had taken place in a town called Bihta. A train had derailed on July 17, 1937. (1937. My father would have been two years old in a village in north Bihar.) Bihta is a small town that I had crossed many, many times on the way from Patna to my birthplace, Ara. How wonderful to read that name in London, in a room where other strangers sat looking at archival documents from Asia and Africa. To encounter names like Koilwar Bridge, another name from my childhood. The report was an indictment of the driver of the train 18 Down, a man named Brinkhurst, who had been going too fast. Page after page of clean, cautious notation, discounting contradictory claims made by the driver and the foreman. I liked the order that was restored by this forensic account. I should add that the principal actors in the drama—the driver, the senior government inspector, the chief engineer, the signal engineer—were all Englishmen. Among the European names in the account, an Indian’s name stands out in the mention of the humble switchman who on the night of the accident was doing his job of switching levers in order to shunting the trains on to the proper tracks. He was Sheopujan Ram. This name gave me as much pleasure as the discovery of my birthplace in that account. The report mentioned that some railway officials had cast doubt on Sheopujan Ram’s statement because he was illiterate, but the honorable Sir John Thom made note of the switchman’s experience and underlined the fact that he had ‘remained unshaken throughout his examination and cross-examination.’ Brinkhurst, I trust, was meted out the punishment he deserved; I don’t really care about him. I am making this post to honor the memory of Sheopujan Ram who had glanced up at the clock and noted the time (3.52 AM) when he had heard the sound of 18 Down approaching and then put his head out of the window to find out that the train had come to a stop because of the accident. This allowed Sir Thom to not only corroborate other evidence of the speed of the train but also fix the exact minute at which the derailment occurred.

I should add that in writing my book my model has been not Sir Thom with his authoritative way with facts (his perfect understanding of the inclination of the line, their alignment, the grasp of fractions of inches, the notation of relevant stats) but the alert, illiterate man from Bihar, Sheopujan Ram. A crucial witness with his eye on the clock and the curiosity to quickly assess reality, remaining faithful to his observation despite the pressure of his circumstance.

I hope you will join me in my train journey.

Eagerly looking forward to this book! I remember you mentioned it during your workshop in August!

Aaahh this honorable Sheopujan Ram..