Late last month, while passing through Delhi, I stopped by to see Ashis Nandy. I’m very fond of Ashis da; during all my earlier visits I had found that there was nothing on which he couldn’t deliver acutely insightful commentary. This time, I began asking Ashis da about creativity in India. Where is it to be found? In response, he said that most social acts are transactional now, there is very little creativity, and it is difficult to mobilize people. All ideologies are seen as hollow. Ashis da has written about our great leader before and as an example of the hollowing out of ideology he cited the case of Modi alleging that opposition leaders are receiving cash from leading businesses. We talked about many things and at one point Ashis da said it wasn’t Gandhi but Savarkar who was now the father of the nation. He had been reading a book by Basil Davidson, The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State, and he had a lot to say about how we in India have suffered under the machinations of the nation-state. Using Mandela as an example, Ashis da spoke about how we need to replace regimes of hate with what he was calling regimes of convivality. In India, in diverse communities, there is still a kind of caring—citing the late anthropologist B.K. Roy Burman, Ashis da said it was because of the civic acts of ordinary people that Indira Gandhi’s Emergency failed. At the end of our conversation, I said to Ashis da that he was older than our country, they have grown old together, and would he please give me a line on how they have aged. He wrote down the line you see above. I wish Ashis da—and India—good health and a long life.

I have been listening to the podcasts of Sheeba Aslam Fehmi. How to create a vibrant public sphere where people’s voice, especially critical voices, are given a free space? I have had a feeling that the podcast was an effort in that direction. During my visit to her home near the Jama Masjid, Sheeba told me about her start as a journalist at a very young age in Kanpur. After the birth of her son, she began working on her doctorate on Islamic feminism at J.N.U. Her scholarship and her writings have been an important part of her identity as a public intellectual. Did she have a message for young women in India? Sheeba wrote above: ‘Listen, girls. Despite all kinds of problems, this phase in our struggle is good for us. What we can think of today as possibilities couldn’t even have been dreamed of by our naanis or daadis. Turn your mind and your thinking into your strength so that you can free yourself from the way in which patriarchy has limited your existence only to your body.’

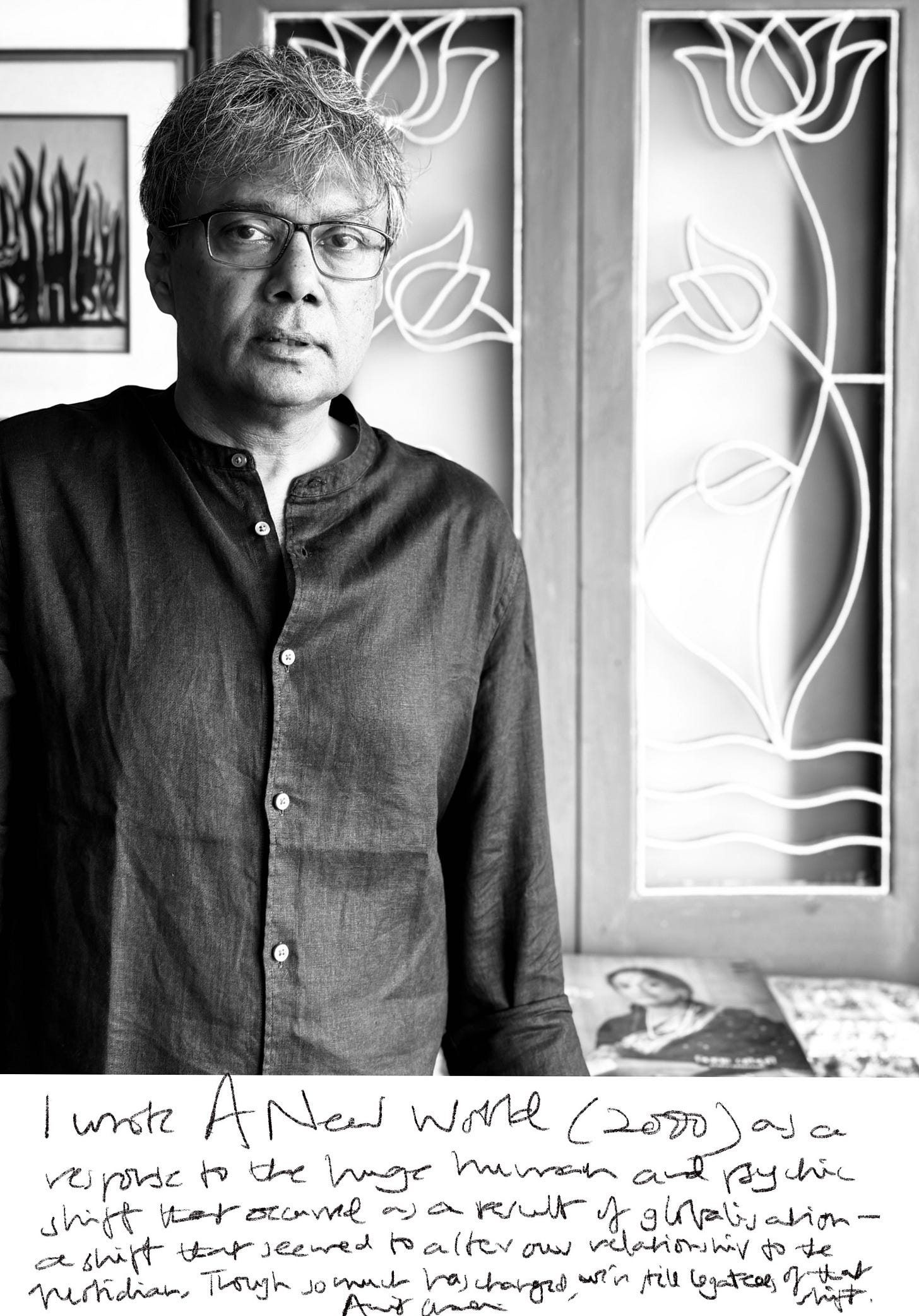

Amit Chaudhuri’s important novel A New World was published twenty-five years ago. In the novel, Jayojit is an economist who has been teaching in the United States; after his divorce, he has returned to Calcutta with his son. They are visiting Jayojit’s old parents. The larger world is always present but only in a partial or oblique way; for instance, while Jayojit is putting away his clothes in a cupboard he notices the section of the newspaper covering the shelf: ‘Something about Marxism and liberalization: the paper couldn’t be very old. The hard-core Marxists and trade unions wanted to know how the Chief Minister would reconcile liberalization with Marxist beliefs; Basu had offered China as an example. Then the paper was covered with clothes.’ What Jayojit is reading in the news is no longer news: more than two decades have passed. Calcutta is now Kolkata. The left government is not in power any more in West Bengal. Internet banking is hugely popular; the volume of online business is exponentially higher; the amount of capital being generated is huge. I asked Amit when we met in Kolkata, Are we not in a new, new world? No, he said, his 2000 novel had been written ‘as a response to the huge human and psychic shift that occurred as a result of globalization’ and ‘though so much has changed, we’re still legatees of that shift.’

If I were preparing a report on India, how would I think about the peripheries? In my chat with Sumana Roy, author of the excellent Provincials, I asked her to explain her affection for Siliguri. (The restaurant where I took this picture is mentioned in her book.) Provincials is a tribute to the creativity and ingenuity of writers and artists in small towns and villages. Sumana is making an appeal (a justified one, I feel) for legitimacy—for those who have their origins outside the cosmopolitan center. Her argument isn’t limited to a particular history or geography but it is particularly relevant at this moment: India is conceiving itself, or at least the ruling party is, in a manner where all the power is concentrated in Delhi, and it is critical that, in the interest of democracy, power is redistributed among the provinces. Which is to say, instead of one person, power is spread among the people. Happy independence day!

aha! very tricky. So 79th celebration but 78 years of independence (altho that is also debatable!)

and greatly enjoyed this post!